Contents

State of Organic Seed (SOS) is an ongoing project to monitor organic seed systems in the U.S. Every five years, Organic Seed Alliance (OSA) releases this progress report and action plan for increasing the organic seed supply while fostering seed grower networks and policies that aim to decentralize power and ownership in seed systems. More than ever, organic seed is viewed as the foundation of organic integrity and an essential component to furthering the principles underpinning the organic movement. We are proud to share this third update.

Executive Summary

State of Organic Seed (SOS) is an ongoing project to monitor organic seed systems in the United States. Every five years, Organic Seed Alliance (OSA) releases this progress report and action plan for increasing the organic seed supply while fostering seed grower networks and policies that aim to decentralize power and ownership in seed systems. This 2022 report is our third update, allowing us to compare new data with our 2011 and 2016 findings.

The data comparisons included in this report provide a snapshot of progress (or lack thereof) and ongoing challenges and needs for expanding organic seed systems and the seed supply they support. More than ever, organic seed is viewed as the foundation of organic integrity and as an essential component to furthering the principles underpinning the organic movement. The authors of this report view organic agriculture as more than a package of production practices, but as a necessary social movement that can create a sustainable and equitable path for our seed, food, and farming systems.

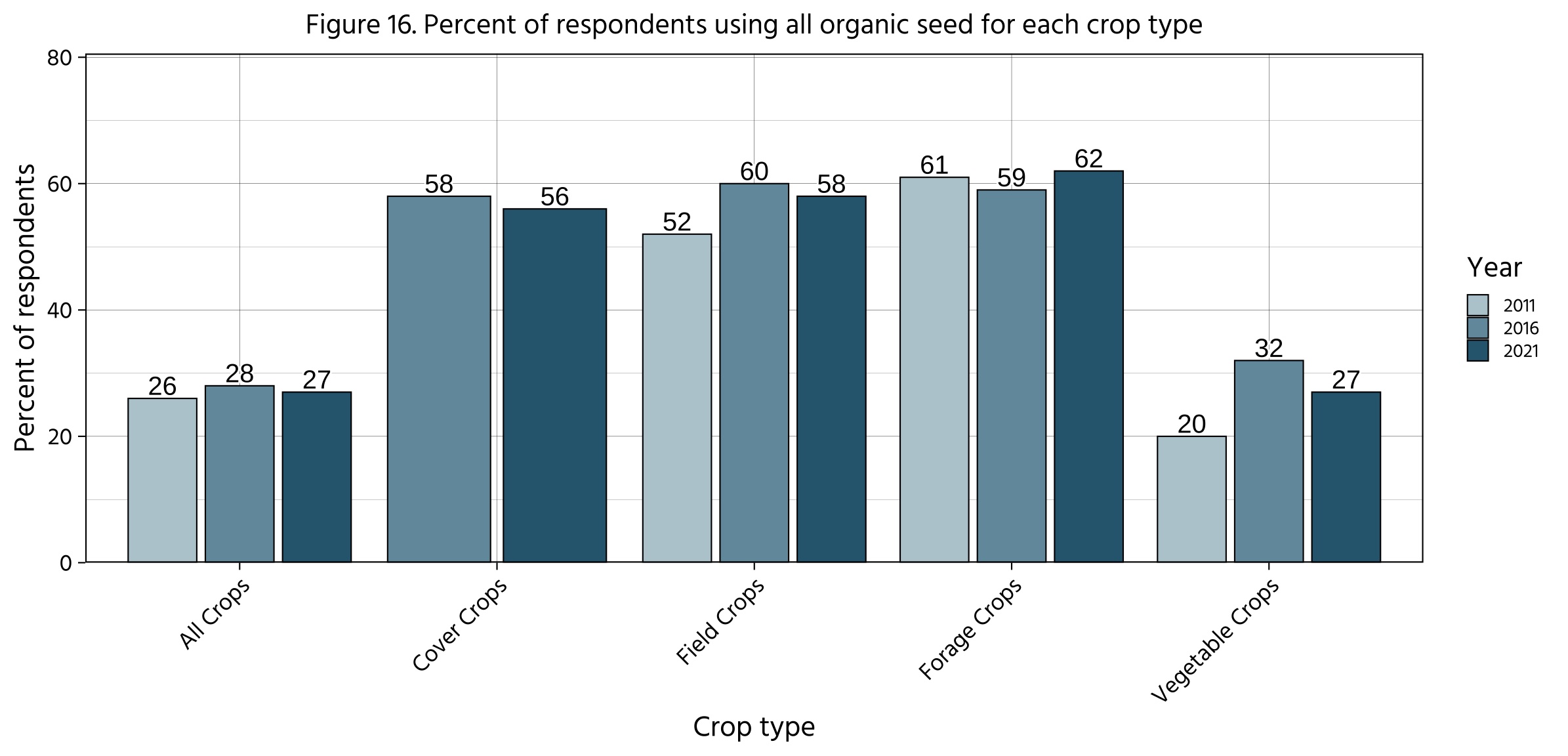

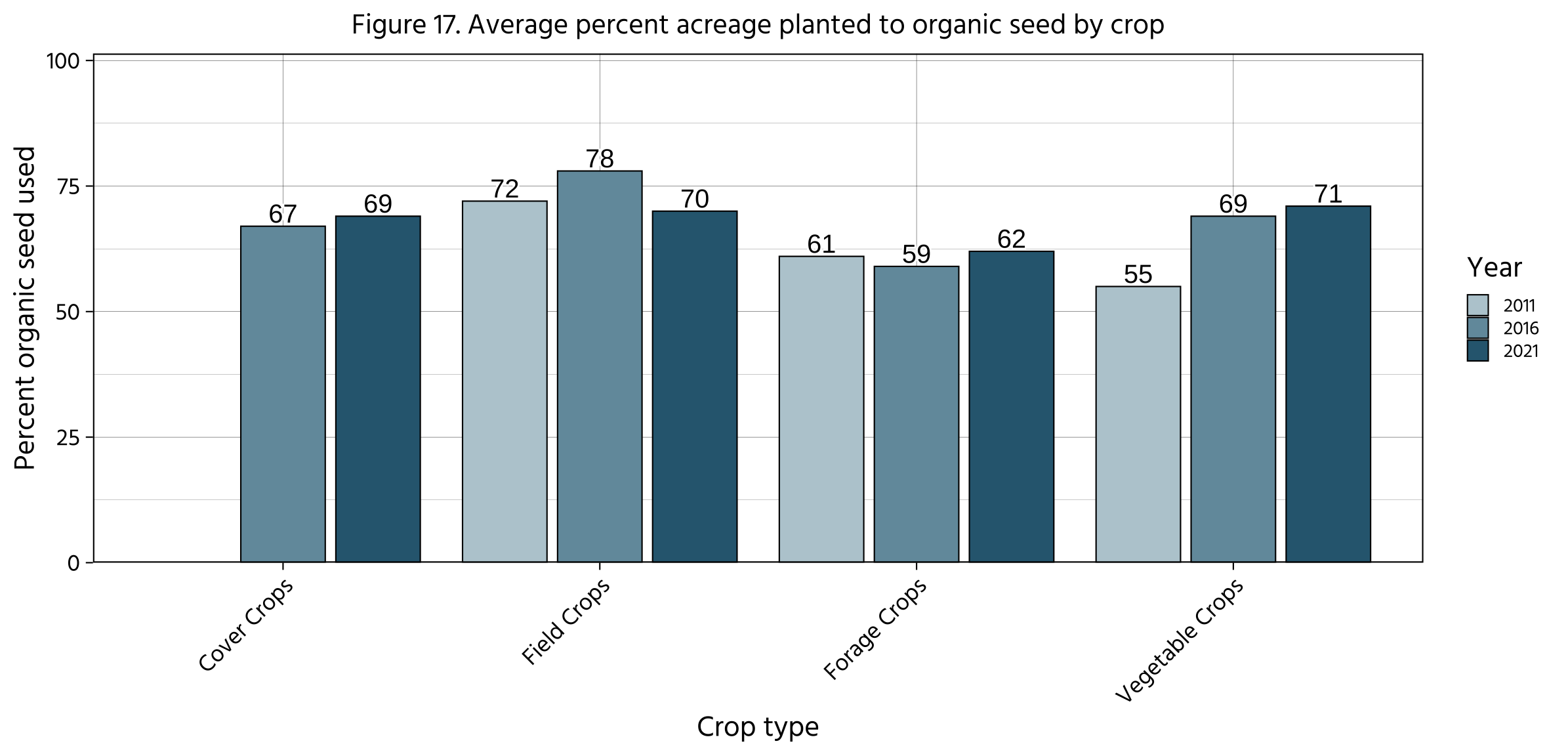

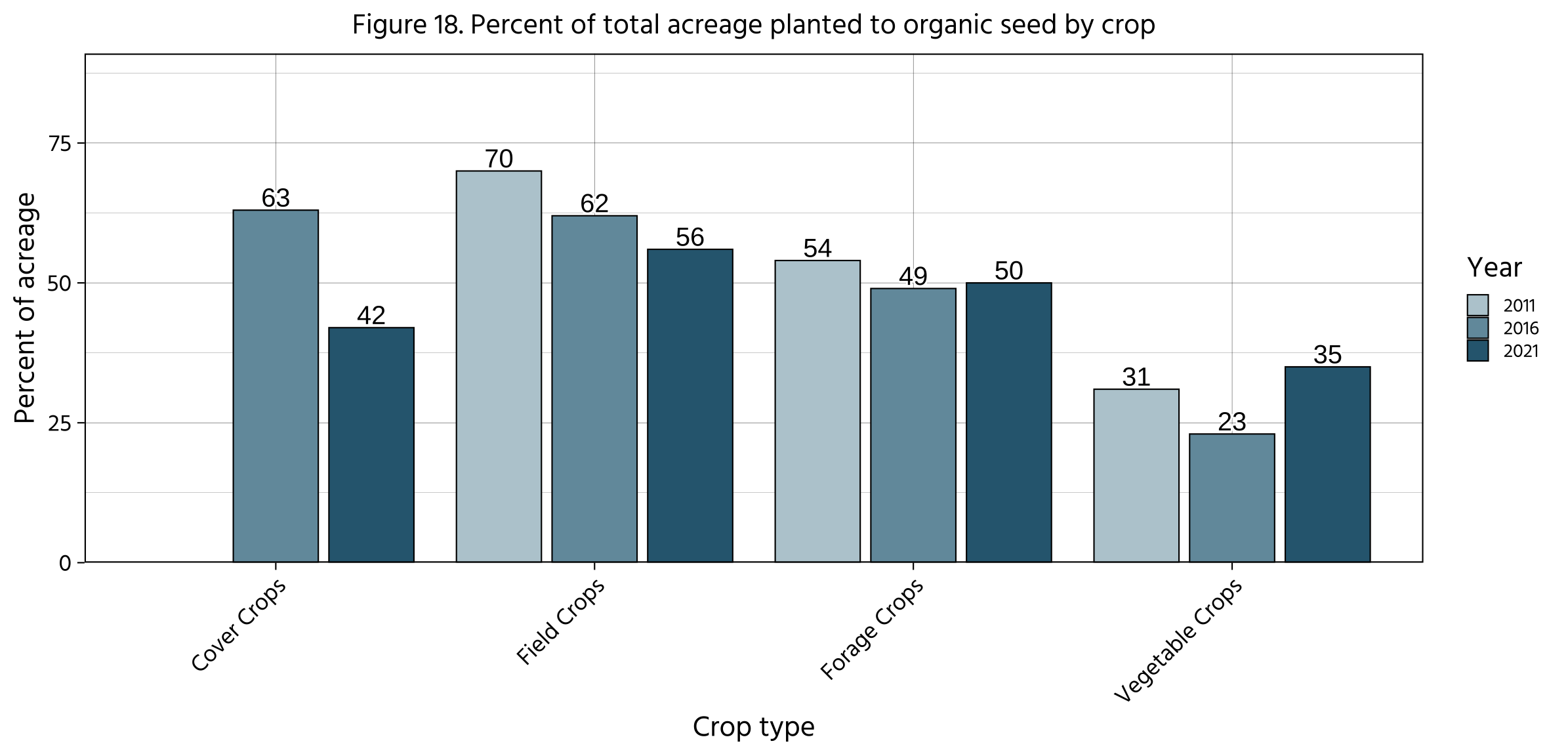

Our newest findings show no meaningful improvement in organic producers using more organic seed.

The organic seed supply has grown tremendously since the National Organic Program (NOP) was established in 2002, which formalized the US organic standards. Certified organic growers are required to source organic seed when commercially available, but our findings show that most organic growers still plant some non-organic seed for at least part (if not all) of their operations. Unfortunately, our newest findings show no meaningful improvement in organic seed usage since our 2016 report.

We arrived at this and other conclusions through a number of data collection methods. SOS is drawn from seven data sets: four different surveys of organic growers, certifiers, researchers, and seed producers/companies; seed producer interviews; a database of organic research project funding; and grower focus groups organized by Organic Farming Research Foundation (OFRF). New to this report is a deeper examination of seed producer/company experiences and research needs, in addition to an analysis of their networks.

Organic seed as a catalyst for change

Seeds are alive and adapt to changing climates through seed saving, selection, and other classical plant-breeding techniques. This adaptation is key for a crop’s survival—mitigating risks for growers and the communities they feed. Organic plant breeding and organic seed are therefore key elements of adaptable and resilient farming systems. When these seeds are grown organically, the climate benefits are even greater. For example, organic seed is produced without fossil fuel-based fertilizers, a major contributor of greenhouse gas emissions.

Organic seed provides other environmental and human health benefits as well. This is most evident when looking at the number and volume of chemical pesticides applied to farm fields–including conventional seed fields–each year that result in harm to non-target organisms, water and soil quality, and human health. Organic seeds are grown without synthetic chemicals and are not treated with synthetic chemical seed coatings, so growers who plant organic seed are choosing to keep pollution caused by synthetic pesticides out of our soils, water, air, and food.

We also believe that a healthy seed system is decentralized, with many decision makers at the table: seed growers/savers, plant breeders, farmers, consumers, chefs, food and seed businesses, Indigenous seed keepers and tribal nations, and others. In important ways, the expansion of organic seed systems has embraced decentralized approaches to plant breeding, seed production, and distribution. And as a social movement, we believe that organic seed can take a distinct path from the dominant conventional seed industry, where consolidation and privatization are key strategies. As the seed industry further concentrates ownership of seed, we see evidence that organic seed growers and their networks are striving to expand the organic seed supply through strategies of decentralized power and ownership to avoid the negative consequences of consolidation and privatization.

Key findings

As mentioned, the organic standards require sourcing of organic seed when commercially available, but most organic producers are still using non-organic seed for at least part (if not all) of their operations. Some key findings include:

Organic producers and their organic seed use

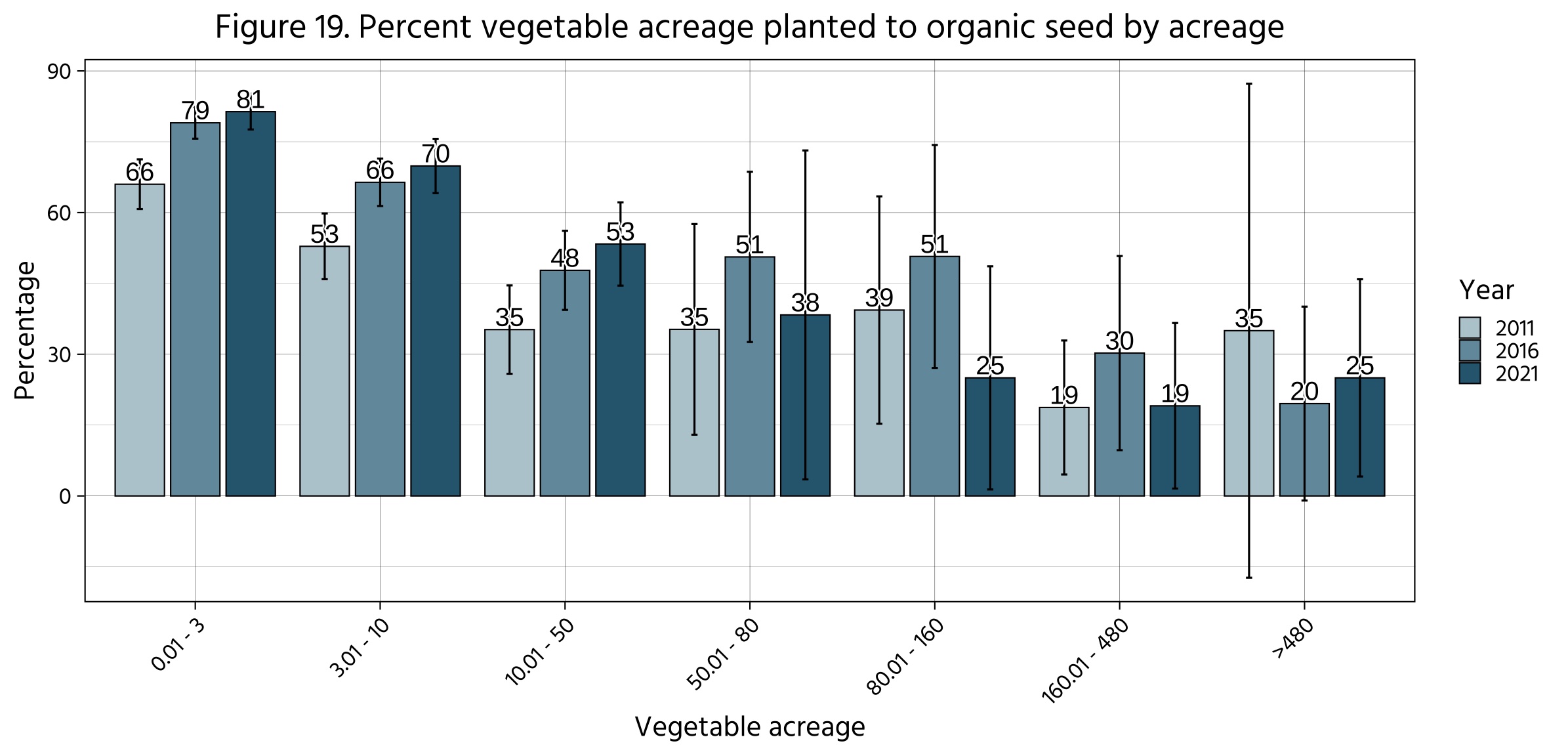

Vegetable producers who grow fewer than 50 acres of crops report using more organic seed. Much like we saw in our last report, the biggest vegetable producers still use relatively little organic seed, and this has a big impact on overall acres planted to organic seed.

Organic seed sourcing in field crops, forage crops, and cover crops remains stagnant. Approximately one third of these growers report increasing the percentage of the organic seed they’re planting, and roughly 40 percent of producers report using about the same amount of organic seed compared to three years ago.

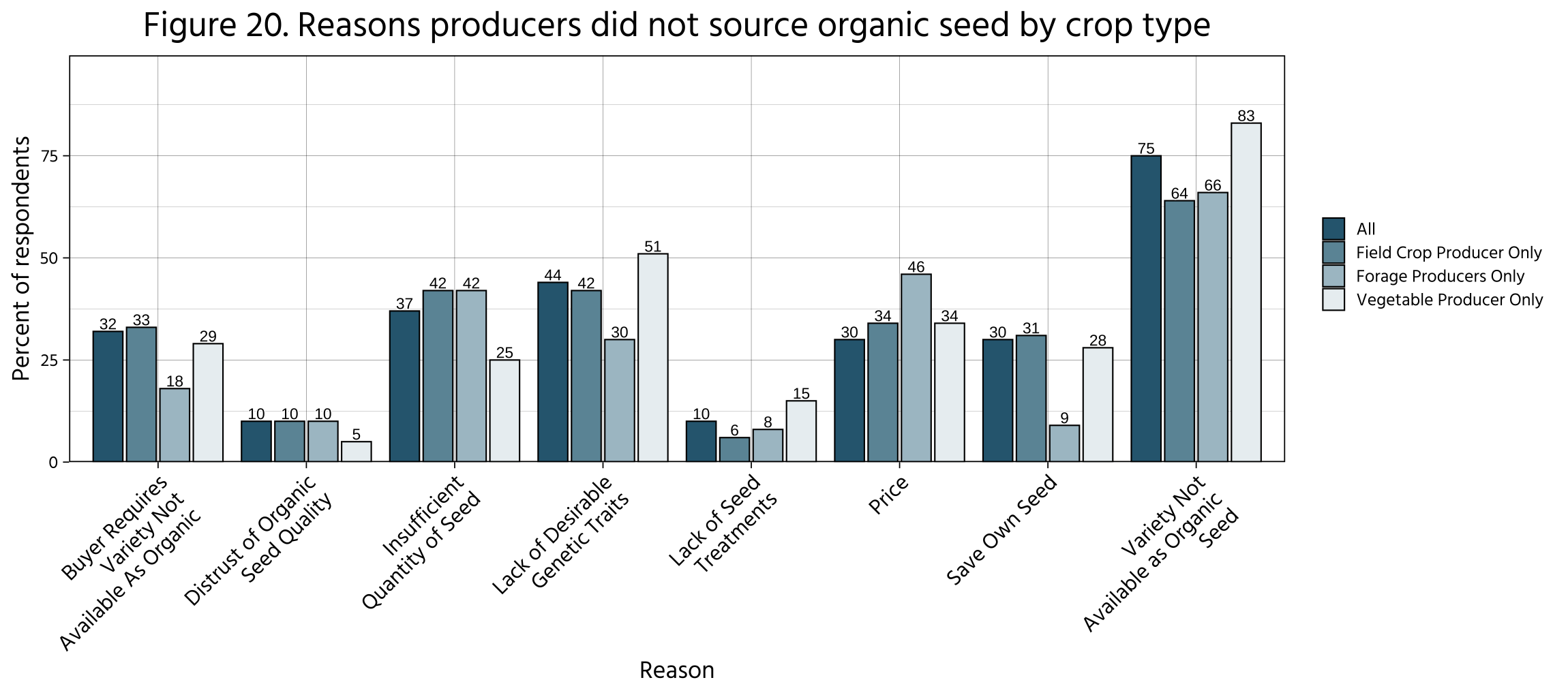

Producers report variety unavailability as their top reason for not sourcing organic seed. Furthermore, certifiers have a hard time identifying what might be substituted as an equivalent variety per the organic seed regulation.

We saw an increase in organic producers reporting a processor/buyer requirement as a factor in not sourcing organic seed. More than 30 percent of respondents identified this as a challenge, and some certifiers also report these processor/buyer requirements as barriers to organic seed sourcing.

Most organic producers source their seed directly from seed companies through websites, catalogs, and sales representatives. A much smaller percentage of organic producers source seed from their own production, stores, processors, buyers, or other farmers.

Organic producers still believe organic seed is important to the integrity of organic food and that varieties bred for organic production are important to the success of organic agriculture. These findings match our last report and demonstrate that growers understand that breeding crops in organic systems is important to their success and to that of the broader organic industry.

Organic seed and breeding research and investments

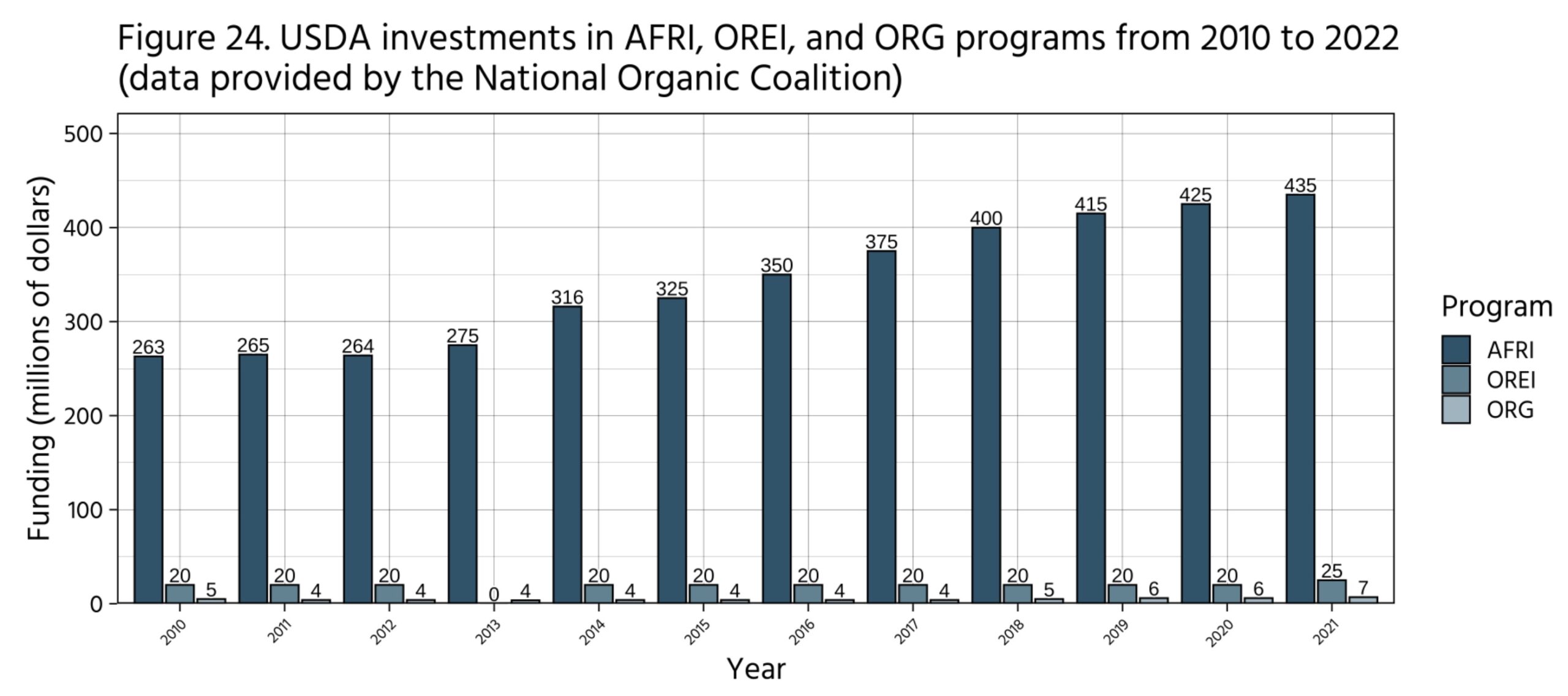

Public investments in organic plant breeding and other organic seed research have increased by $39 million in the last five years alone. In our first report, we documented $9 million in investments between 1996 and 2010 and saw this increase to $22 million between 2011 and 2016. Our most recent finding demonstrates good progress toward funding this critical area of plant breeding to support organic seed systems and the organic growers who rely on them. Still, public investments in organic seed systems fall short in light of the growing demand for organic products.

The bulk of public research investments come from USDA OREI and are dedicated to breeding and variety trials. Multi-regional projects receive the most funding, as researchers across the country collaborate to support organic research.

More public plant breeders are having success releasing new organic varieties. Public plant-breeding programs help fill market gaps unmet by the private sector, including in organic seed, but more public investments are needed to ensure these programs remain viable and responsive to the needs of growers in their regions. Challenges include staffing and capacity for researchers to carry out their projects.

Our data indicates that organic seed priorities pursued by researchers generally align with the demands of organic producers. In particular, organic producers identified a number of vegetable and field crops as needing plant-breeding attention, and these are the most popular crop categories being researched – with disease resistance and yield traits taking priority.

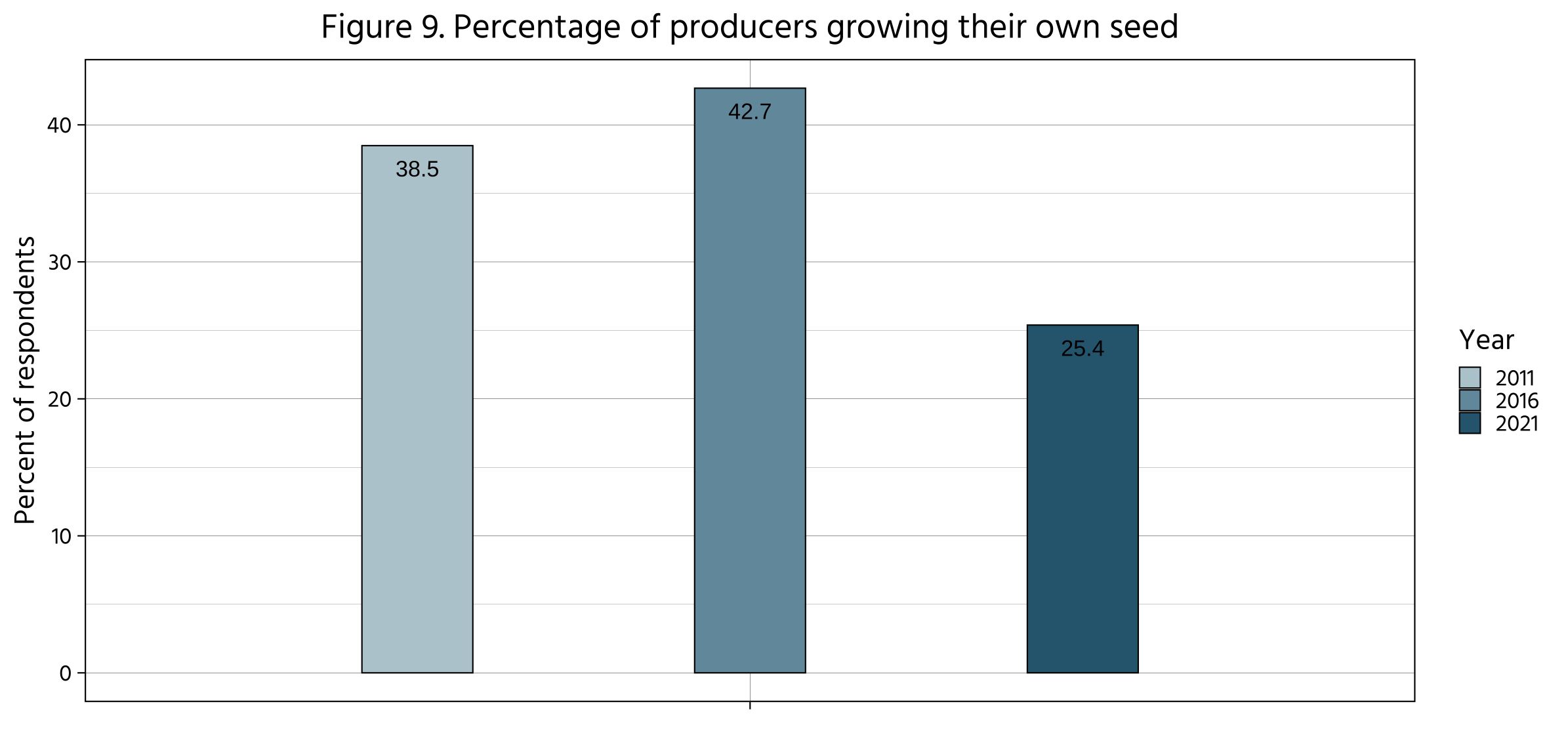

Fewer producers report saving seed for either on-farm use or to sell commercially compared to our last report. A quarter of farmers are using saved seed, and nearly half are producing seed for on-farm use or to sell commercially. Despite a significant decrease in producers reporting saving and/or producing commercial seed, most farmers responding to our organic producer survey are interested in learning how to produce seed commercially. The lack of training, economic opportunity, and seed processing facilities were the top factors keeping farmers from growing organic seed commercially.

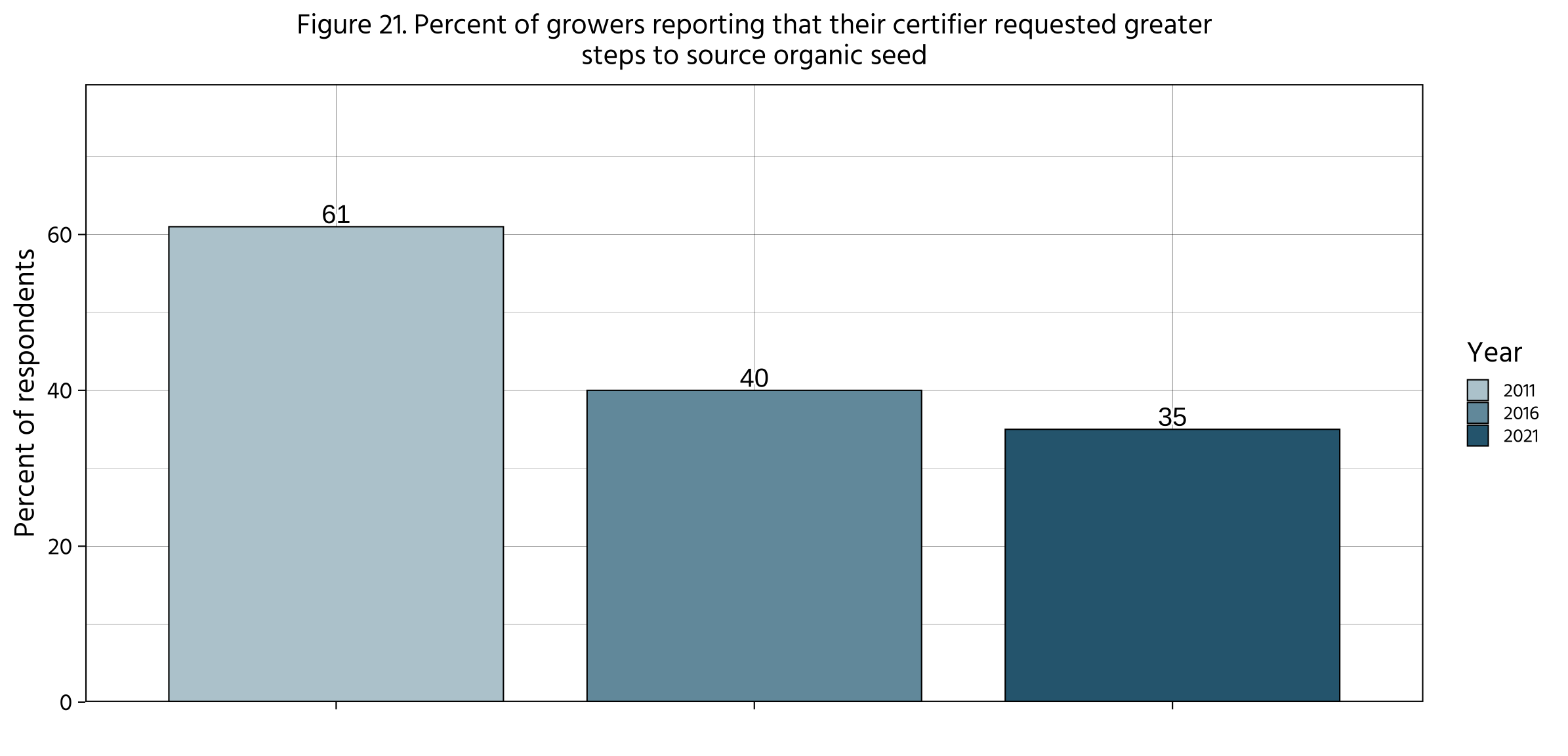

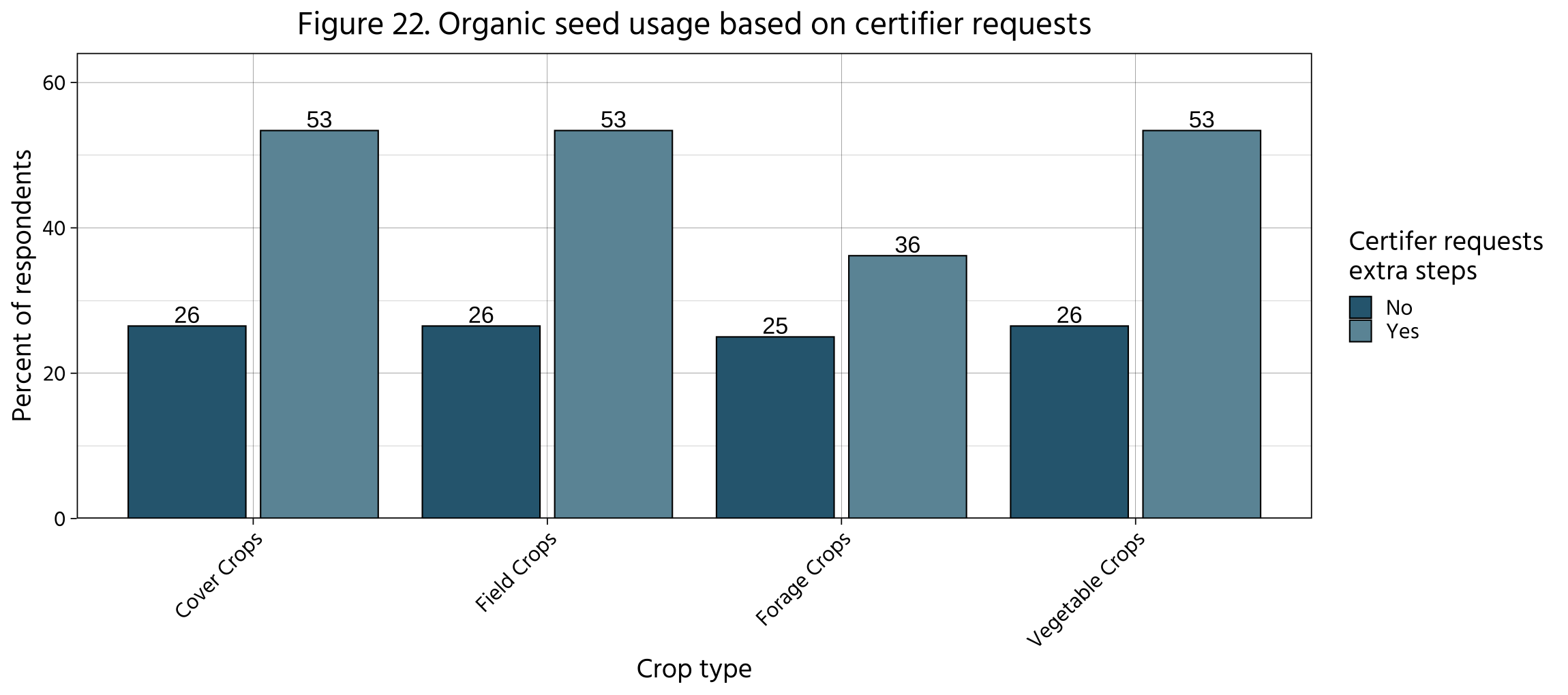

Fewer producers report that their certifiers are requesting they take extra measures to source more organic seed. This is an important finding, since our data also shows that when certifiers encourage producers to improve their organic seed sourcing, these organic producers indeed source more organic seed.

Perspectives from organic seed producers/companies

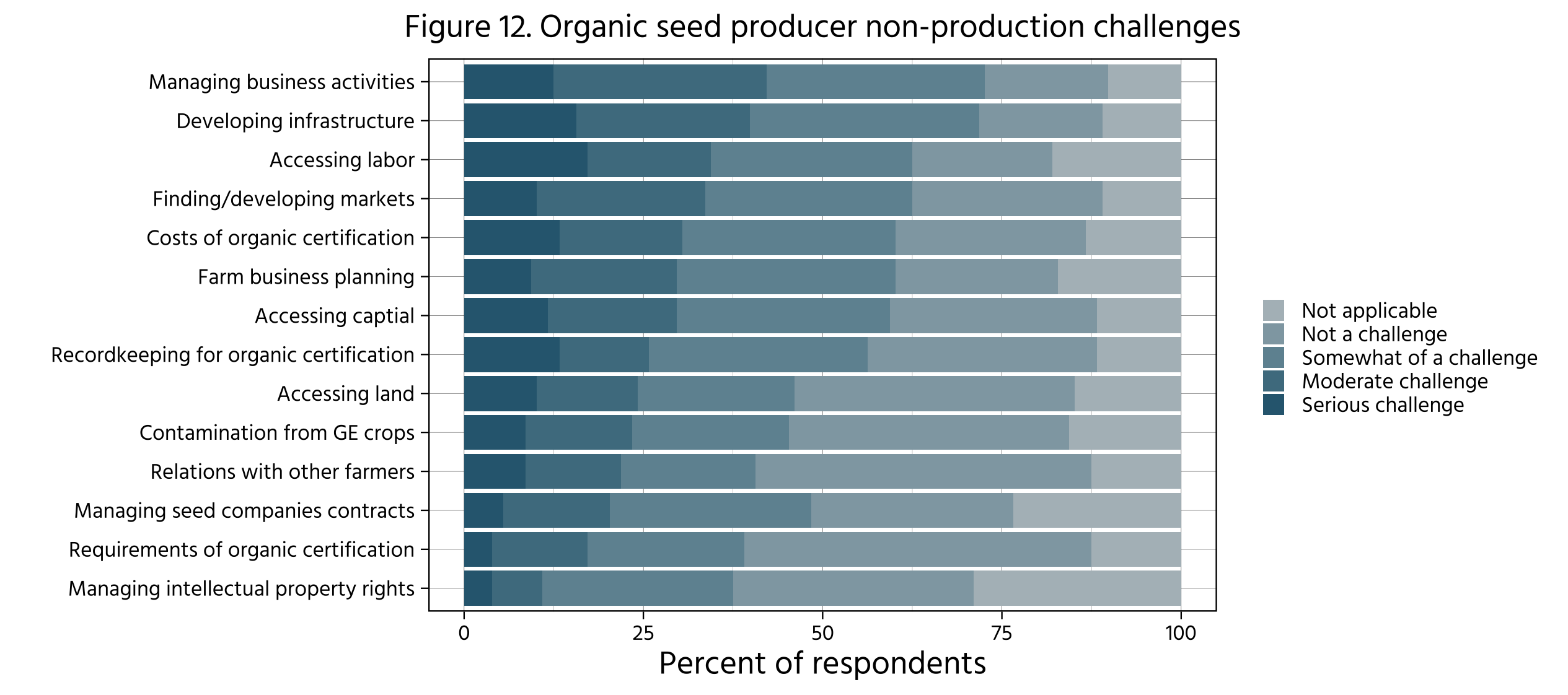

Seed producers face a number of production and non-production challenges. The production challenges reported include estimating and achieving yields; controlling weed, pest, and disease pressure; and managing climatic effects. Outside of production, managing business activities and finding markets, developing infrastructure, and finding and retaining skilled labor all rank high on the list of challenges.

Climate change is severely impacting organic seed growers. Numerous growers reported extreme weather events and unpredictable changes in their climate as a serious challenge. Policy actions and research investments are needed to mitigate the impacts and increase the climate robustness of our crops and seed systems.

GMO contamination remains a concern of organic producers and seed companies. Maintaining high genetic integrity of organic/non-GMO seed used in organic farming is important to organic producers and seed producers/companies, but organic policy solutions are difficult to identify. True “coexistence” is only possible when manufacturers and users of GMO crops share the responsibility for preventing contamination of organic and other non-GE seed.

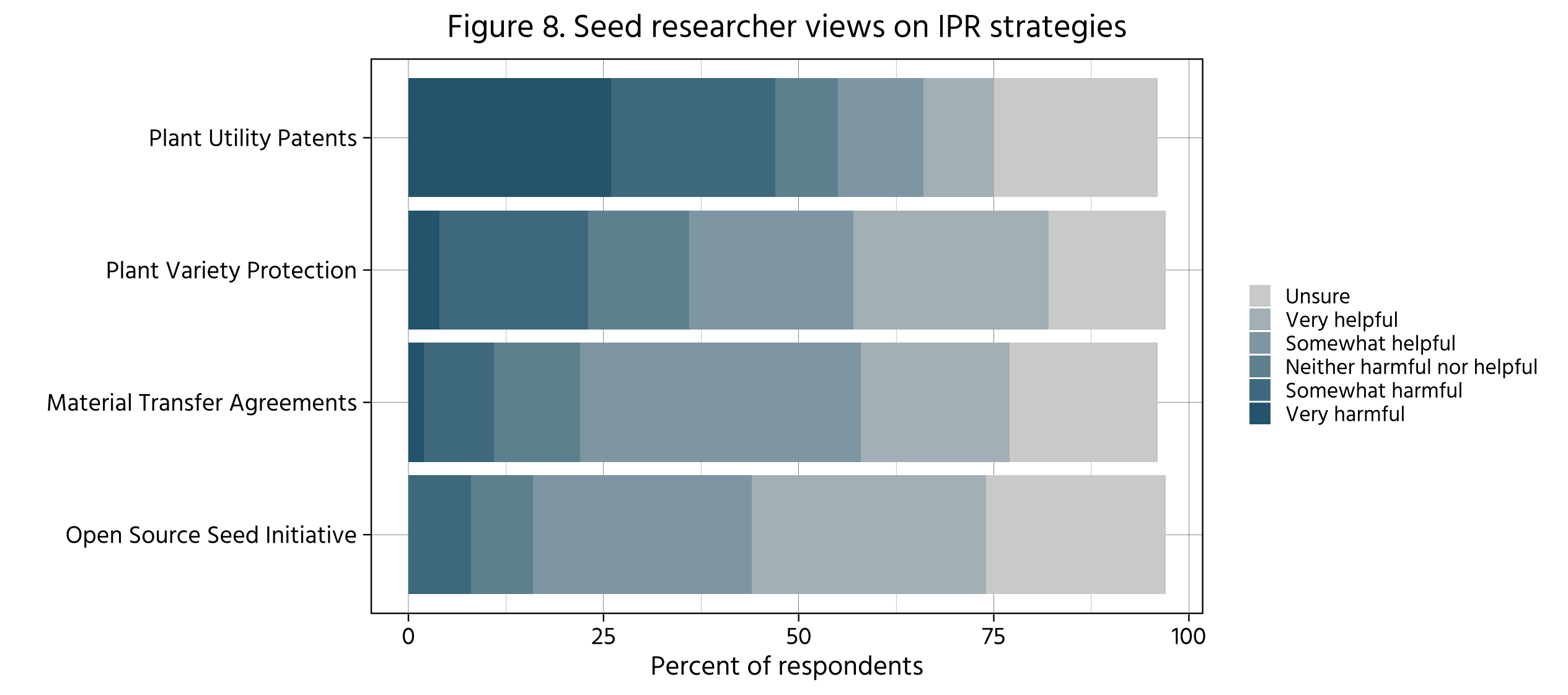

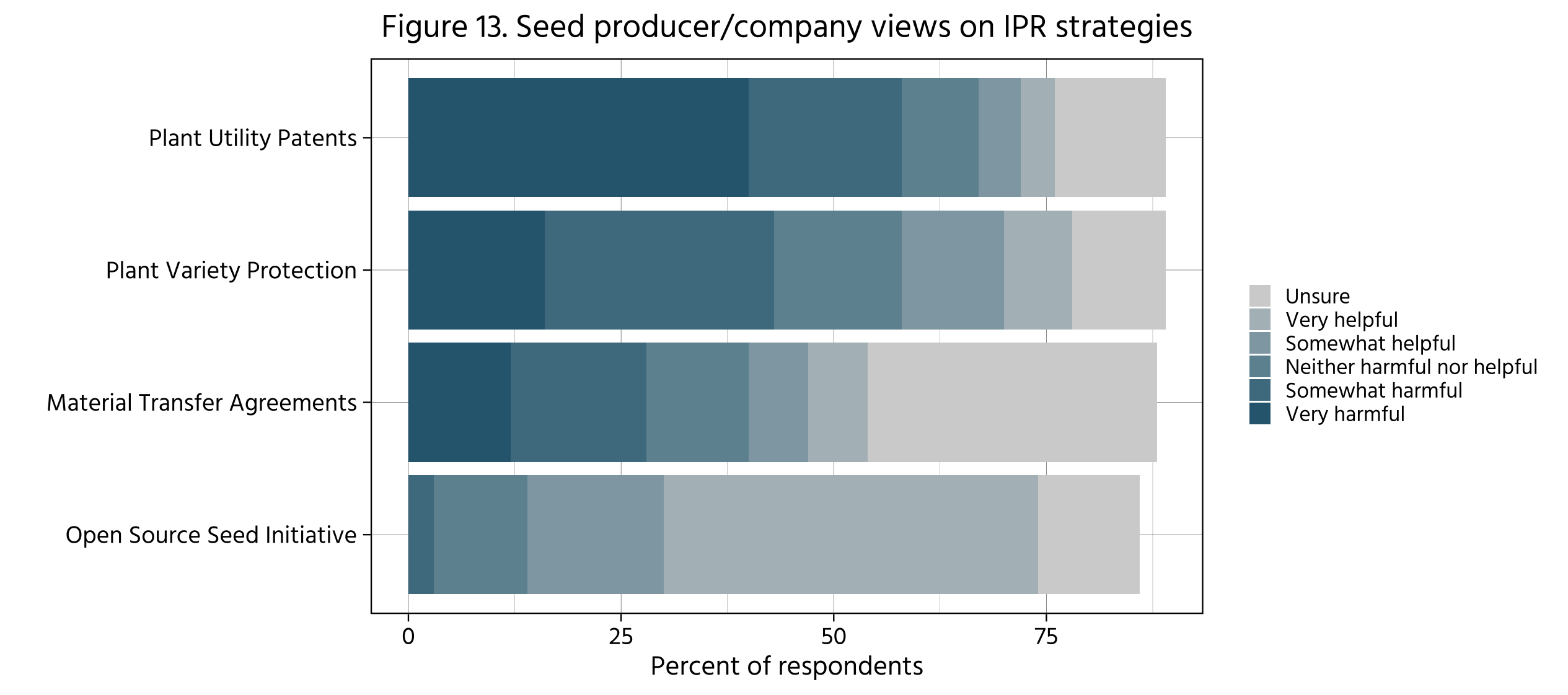

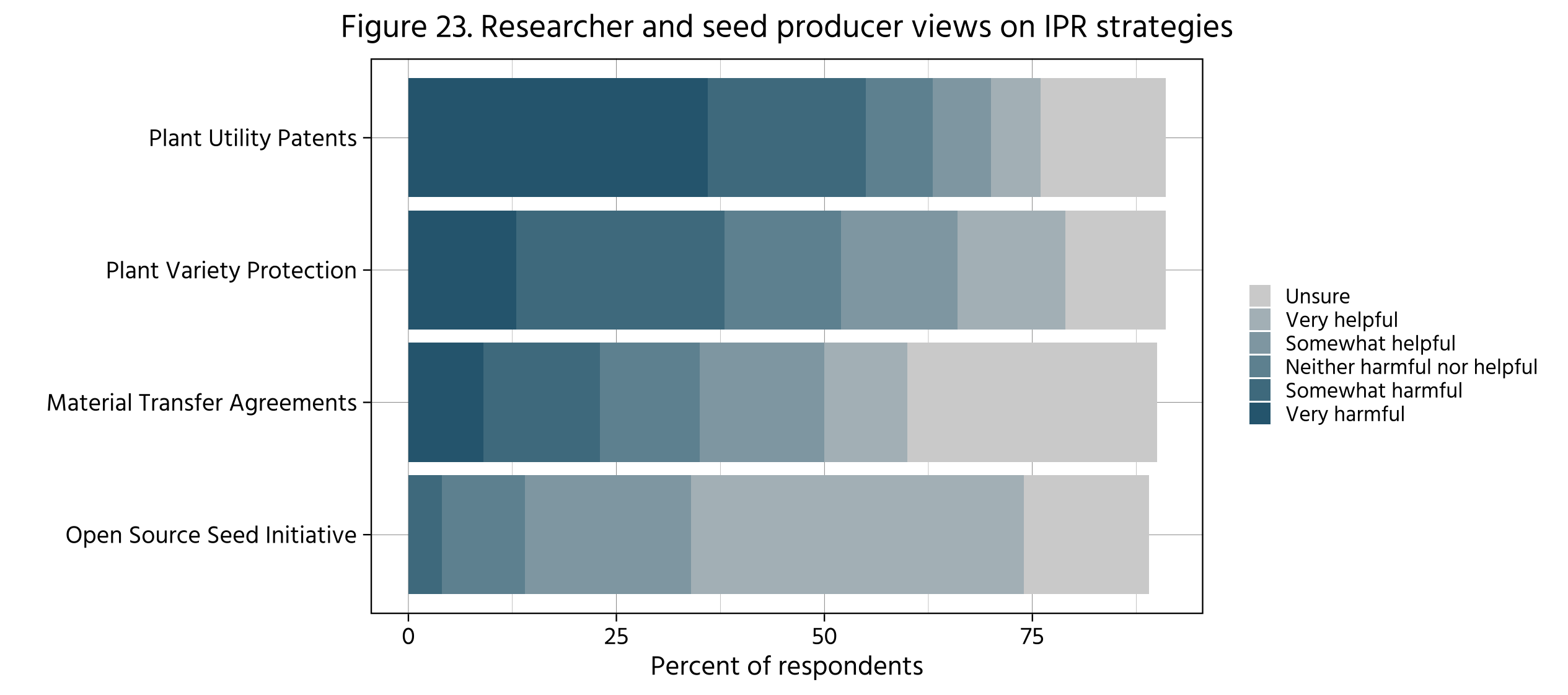

Seed producers/companies and organic researchers view utility patents on seed as the most harmful form of intellectual property right (IPR) associated with seed. They also viewed the Open Source Seed Initiative (OSSI) pledge as most helpful.

A major gap in data and resources is a reliable, national database of all commercially available organic varieties. A more robust organic seed database would support organic seed sourcing and enforcement of the organic seed requirement and could serve as a market assessment of commercial availability.

Seed producers identified common elements when asked to envision a resilient seed system. In particular, seed producers would like to see decentralized regional communities of seed growers that can work together to share knowledge, access markets, and maintain diverse, productive, and adapted seed.

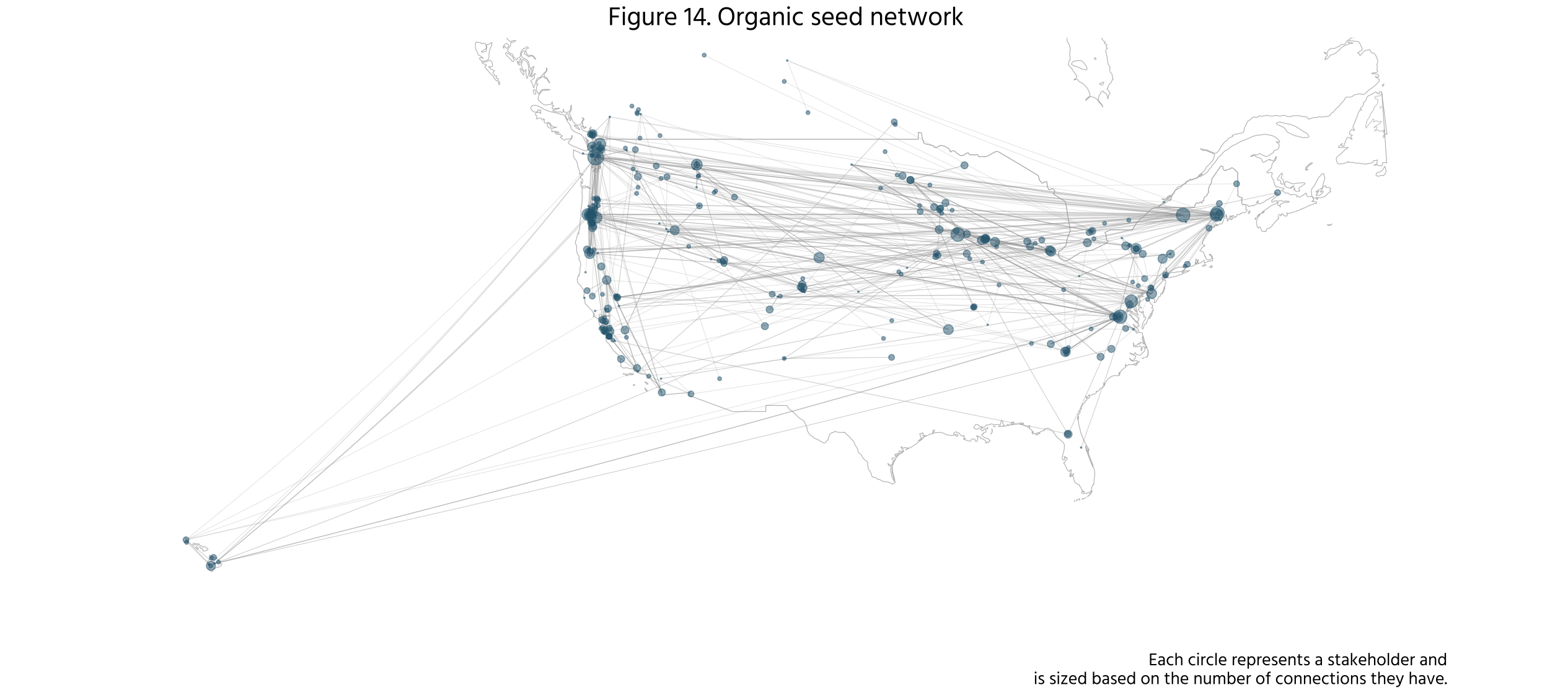

The current structure of seed networks across the US mostly reflects a resilient seed system. However, regions other than the West are still small and developing, and resources along the supply chain could stand to be diversified.

All seed networks rely on the National Plant Germplasm System. Seed producers/companies access these public seed collections for purposes of adaptation, breeding, and seed production, underscoring the importance of ensuring adequate funding, access, and accountability within this system.

Top recommendations

A longer list of recommendations can be found in the conclusion of the report. We hope these recommendations will serve as an action plan for increasing the organic seed supply while fostering seed-grower networks and policies that aim to decentralize power and ownership in seed systems. The recommendations that stand out as most timely include:

- Public research investments in organic plant breeding and seed initiatives should continue to increase. Research agendas should also be diversified to prioritize seed- producer challenges identified in this report.

- Train more organic seed producers and support existing producers to ensure that organic seed production capacity continues to grow in the US.

- The organic seed regulation should be strengthened and consistently enforced, regardless of farm size, and buyers/processors who contract with organic producers to use specific varieties should be held accountable to the organic seed regulation.

- Organic seed stakeholders should advocate for policy initiatives that aim to decentralize power in agriculture and advance equity and justice within food and farm policies, programs, and leadership.

Introduction

Nearly twenty years have passed since the US organic regulations went into effect under the oversight of the National Organic Program (NOP). The success of the organic label has been monumental, and consumer demand for organic products shows no sign of slowing. As the highest-integrity food production standard available, this is good news.

When the NOP launched in 2002, the new regulations contained an aspirational goal: to require organic growers to use organic seed. Because few organic seed suppliers existed at the time, the regulations allowed growers to source seed that wasn’t certified organic when they could demonstrate a lack of commercial availability of organic seed. This leeway still exists, but the availability of organic seed has increased tremendously over the past two decades as organic seed systems have taken root.

State of Organic Seed (SOS) is an ongoing project to monitor organic seed systems in the US. Every five years, Organic Seed Alliance (OSA) releases this progress report and action plan for increasing the organic seed supply while fostering seed grower networks and policies that aim to decentralize power and ownership in seed systems. More than ever, organic seed is viewed as the foundation of organic integrity and an essential component to furthering the principles underpinning the organic movement. We are proud to share this third update.

Beyond a regulatory requirement

The organic food market experienced incredible growth in 2020, with sales surpassing $56 billion, representing more than 12 percent growth compared to the previous year. The organic seed market has also grown in recent years due to this organic food market growth, as well as a dramatic increase in gardening during the COVID-19 pandemic (see “The COVID-19 pandemic spurs historic seed sales”). As we celebrate these market successes, we may lose track of the broader benefits of expanding organic seed systems that support the flourishing organic industry.

Seeds are alive and adapt to changing climates through seed saving, selection, and other classical plant-breeding techniques. This adaptation is key for a crop’s survival—mitigating risks for growers and the communities they feed. Organic plant breeding and organic seed are therefore key elements of adaptable and resilient farming systems. When these seeds are grown organically, the climate benefits are even greater. Beyond mitigating the impacts of our warming planet, organic practices also reduce greenhouse gas contributions. For example, organic seed is produced without fossil fuel-based fertilizers, a major contributor of greenhouse gas emissions.

In addition to adapting crops to changing climates, organic plant breeding provides growers other benefits. The challenges inherent in organic farming are different from those in conventional systems, where synthetic pesticides and fertilizers are commonly used to control pests and diseases and to provide plant nutrition. Seed provides the genetic tools to confront these day-to-day challenges in the field, and some research shows that breeding plants in the environment of their intended use—a targeted region or production system, such as organic—allows for crops to perform better in those environments. Furthermore, many organic plant-breeding projects embrace participatory models, where farmers collaborate with formal plant breeders to share knowledge, skills, and priorities. Participatory plant breeding can result in higher-quality organic seed and can provide farmers the skills they need to develop and improve their own varieties.

We have to work together to shift power from agrochemical interests to organic farmers.”

Ira Wallace, Southern Exposure Seed Exchange

Farming has a huge impact on our environment and on human health. This is most evident when looking at the number and volume of chemical pesticides applied to farm fields each year and the resulting harm to non-target organisms, water and soil quality, and human health. As one example, neonicotinoids are the most widely used insecticides in the US. Most neonics enter the environment as a seed treatment, where seeds—the majority of corn seed, for example—are coated with an insecticide prior to planting. Studies show that neonic seed treatments, which are often paired with fungicides, impair the natural defense systems of pollinators and other insects, reducing their populations and putting food crops that rely on pollinators—35 percent of the world’s food crops—at risk.

In 2021, the state of Nebraska sued an ethanol plant for improper storage and disposal of 84,000 tons of neonic-treated seeds. Seeds treated with synthetic chemicals are considered too toxic to use as animal feed or to spread on fields. Instead, the chemicals were piled up on the ethanol plant’s property and they leached into the ground and water supply, and the odor caused some local residents to suffer health impacts. Organic seeds are grown without synthetic chemicals in the field and are not treated with synthetic chemical seed coatings; growers who plant organic seed are choosing to keep pollution caused by synthetic pesticides out of our soils, water, air, and food.

Why is organic the highest-integrity food production standard?

Organic certification is a voluntary process designed to verify every step of the organic supply chain in accordance with federal regulations. It is the most comprehensively regulated and closely monitored food production system in the US. Organic farms and businesses must adhere to the same strict practices regardless of size. The regulations are monitored and enforced by the US Department of Agriculture’s National Organic Program. While organic certification isn’t a good fit for every operation or business, the organic standards provide the strongest food production label available to us today, and certification therefore serves as one of the many solutions to improving the health and resiliency of our food and agricultural systems.

We also believe that a healthy seed system is decentralized, with many decision makers at the table: seed growers/savers, plant breeders, farmers, consumers, chefs, food and seed businesses, Indigenous seed keepers and tribal nations, and others. In important ways, the expansion of organic seed systems has embraced decentralized approaches to plant breeding (e.g., participatory breeding models), seed production (e.g., regional seed grower networks), and distribution (e.g., new seed businesses continue to emerge). Increasingly, chefs, retailers, and food companies are involved in variety tastings and evaluations—identifying organic seed and food market gaps—and even in organic plant-breeding projects. This diversity of decision makers fosters a participatory and decentralized nature to organic seed systems that results in varieties with aesthetic and culinary qualities that are desired by consumers, while also addressing the agronomic challenges of organic farmers.

As a social movement, we have long believed that organic seed can take a distinct path from the dominant conventional seed industry, where consolidation and privatization are key strategies. As the seed industry further concentrates ownership of seed, we see evidence that organic seed growers and their networks are striving to expand the organic seed supply through strategies of decentralized power and ownership to avoid the negative consequences of consolidation. These consequences have included less choice in the market, higher seed prices, genetic uniformity in our fields, restrictions on seed saving and research, and very little transparency. By contrast, organic seed systems have an opportunity to be defined not by what they exclude—such as genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and synthetic chemical pesticides—but by what they embrace: collaboration, cultural heritage, diversity, fairness, health, beauty, and hope.

Project objectives and principles

The SOS project is guided by the following objectives, each of which contributes to our primary goal of expanding grower access to organic seed:

- Improve organic seed stakeholders’ understanding of the barriers and opportunities in building organic seed systems (stakeholders include organic seed growers/savers, organic farmers, plant breeders, certifiers, the seed and food industries, extension officers, researchers, and others).

- Build regional seed networks that support a national supply chain of organic seed.

- Help organic farmers meet the NOP organic seed requirement.

- Advocate for a stronger organic seed regulation to increase organic seed sourcing with the goal of eventually achieving 100 percent usage on all organic acreage.

- Support regulatory approaches that protect organic seed from contamination by excluded methods (e.g., GMOs) and prohibited substances without unintentionally damaging the organic seed industry.

- Improve how seed is managed, both privately and publicly, to reduce concentration of ownership and stimulate competition and innovation, including addressing problematic intellectual property rights (IPR) associated with seed.

- Address barriers to organic agriculture and the seed market faced by Black, Indigenous, Asian and Pacific Islander, Latin American, Multi-Racial, and LGBTQIA+ growers who currently face prejudice and endure harm.

- Identify urgent organic seed research and education needs and increase investments to fund these and other priorities to improve organic seed availability, quality, and integrity.

While the data contained in this report is based on certified organic production, OSA’s vision for organic seed systems includes seed growers who are committed to organic and agroecological practices and principles, whether certified or not. We believe strongly in organic certification and the benefits to growers, consumers, and the planet. We also recognize that organic certification is not the right fit for every grower and that barriers to certification and the organic market exist.

Some of these barriers include inequitable land ownership and long-standing institutional racism. For example, only 3 percent of organic farmers are people of color, and USDA data show that organic farms with white operators earn significantly more than other racial groups. Furthermore, the representation of farmers of color in organic is lower than the nationwide rate, where 4.6 percent of all farmers are people of color. These realities bring racial inequities within agriculture into sharp relief.

Barriers to organic certification include the three-year transition period, which presents a significant financial hurdle because growers face higher production costs without receiving organic price premiums during the transition. Other barriers include access to capital, training, and technical assistance, and keeping up with the demands of the certification process.

We believe fostering diverse and healthy seed systems is not possible without reckoning with the legacies of harm to people of color in the US, including the history of harm in agriculture. This includes acknowledging that the organic industry contributes to inequity and injustice in our food and agricultural systems and needs to shift power to those historically marginalized in the organic food system. Systemic racism negatively affects all communities—and that includes seed communities. It is important to examine the histories and contributions of seed saving and sharing among Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) and the role these legacies still play in our food systems.

We view organic agriculture as more than a package of production practices, but as a necessary social movement that can create a sustainable and equitable path for our food and agricultural systems.

As such, we have updated the principles guiding this project to fill specific social justice gaps that we humbly acknowledge were absent in previous SOS reports. We view organic agriculture as more than a package of production practices, but as a necessary social movement that can create a sustainable and equitable path for our food and agricultural systems. The following principles for fostering the organic seed movement were first established in our 2011 report and have been evolving with stakeholder input ever since:

- Organic food should begin with organic seed.

- Seeds are a vital yet vulnerable natural resource that must be respected and managed in a manner that enhances their long-term viability and integrity.

- The maintenance and improvement of genetic and biological diversity are essential for the success of sustainable, healthy food systems and the greater global food supply.

- The equitable exchange of plant genetics, with appropriate acknowledgement, consent, and compensation, enhances innovation and curtails the negative impacts of concentrated ownership and consolidated power in decision making.

- Growers and their communities have the right to determine whether, and how, culturally important seeds are used and shared to avoid biopiracy.

- Sharing information enhances research and leads to better adaptation of best practices.

- Grower participation in decision-making—in the field and in policy—results in the co-creation of knowledge and shared solutions.

- Action must be taken to remove structural barriers to a just and equitable seed and food system.

- Agricultural research should serve more than one goal and should strive to increase benefits for all living systems, including soil, plants, animals, and humans.

- Public institutions and public employees should serve the country’s agricultural needs, particularly the diverse and alternative systems less supported by the current economic system.

- Growers have inherent rights as agricultural stewards, including the ability to save, own, and sell seeds, and are key leaders in developing best practices, applicable research, and agricultural regulations and policy that affect them and the future of seed.

- Indigenous knowledge should be recognized as the foundation of organic farming and agroecology and uplifted in partnerships and leadership.

- The precautionary principle of protecting food systems from harm when scientific investigation has found potential risk helps safeguard food security in the future.

These principles suggest inherent benefits to developing organic seed systems. These benefits go beyond helping certified organic growers meet a regulatory requirement to source organic seed and extend to positive impacts on our climate, the environment, human health, and society.

Data collection methods

This report is a tool for monitoring progress toward meeting the organic seed needs of organic growers in the United States. We hope it also helps readers understand the intersection of various stakeholders involved in organic seed systems and how to support their success (see “How to use this report”). The report’s findings are drawn from seven data sets: four different surveys for organic growers, certifiers, researchers, and seed producers (which includes seed companies); seed producer interviews; a database of organic research project funding; and grower focus groups organized by Organic Farming Research Foundation (OFRF). Our methods are further described in the appendices.

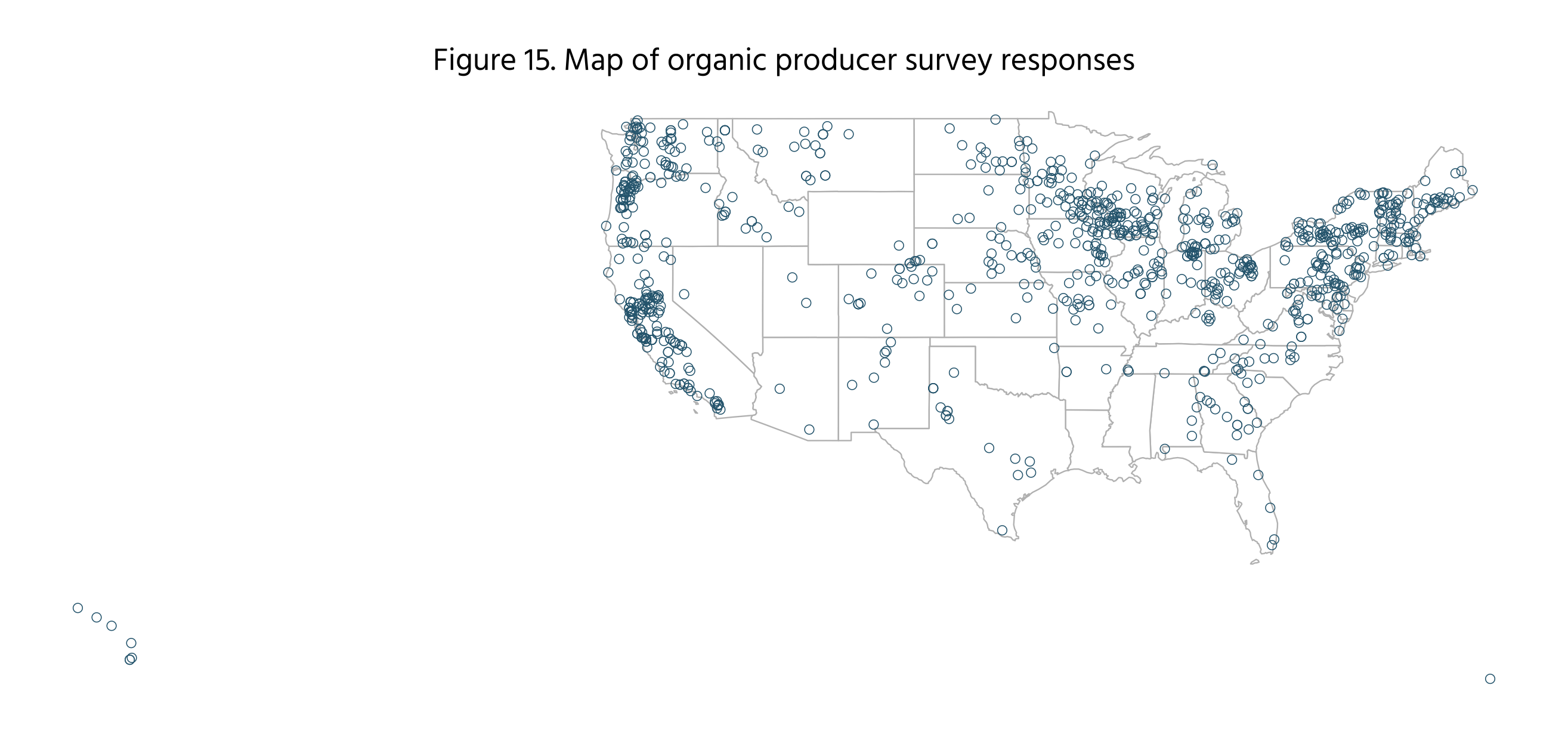

| Organic producer survey | 1,059 certified organic crop producers responded to the OSA/OFRF survey in 2019 and 2020. The survey included questions on demographics, organic seed usage, and opinions on organic seed, plant breeding, IPR, and genetic engineering. A similar survey was distributed for the 2016 and 2011 reports. |

| Certifier survey | 25 individuals representing 22 Accredited Certifying Agencies responded to our survey in 2020. The survey included questions on how the organic seed requirement is being enforced, the challenges ACAs face in enforcement, and their ideas for how to make enforcement more consistent. A similar survey was distributed for the 2016 report. |

| Researcher survey | 51 researchers working in organic breeding or organic seed research responded to our survey in 2021. The survey included questions on their research, their networks, and their perspectives on resilience, climate change, and IPR. A similar survey was distributed for the 2016 report. |

| Seed producer and company survey | 127 organic seed producers and organic seed companies responded to our survey in 2020. The survey included questions on demographics, challenges, research needs, their networks, and their perspectives on resilience, climate change, and IPR. |

| Research investments analysis | We searched and compiled USDA program and foundation funding lists of public organic seed and breeding projects. Projects were categorized according to topic, region, funding source, and crop type. |

| Seed producer interviews | 26 of the seed producers who responded to the seed producer survey agreed to a follow-up interview. Interviewees provided additional details on the challenges and research needs reported in their responses to the seed producer surveys. |

| Grower focus groups | OFRF led 16 focus groups representing more than 100 certified organic and transitioning producers between 2020 and 2021. |

Despite extensive data-collection efforts, we know that holes in our research and analysis exist. The biggest gap continues to be market data on the commercial availability of organic seed. A comprehensive, reliable database of organic seed—or a regular market assessment—would help us more fully understand the state of the organic seed supply and where gaps exist.

How to use this report

If you are an organic seed grower, or thinking about growing organic seed, we hope this report informs your understanding of organic seed systems, how other organic seed growers find support and success through various networks, and the important role that seed policy plays in our seed systems.

If you are an organic certifier, inspector, or regulator, we hope this report informs your understanding of trends in organic seed sourcing and enforcement and the important role you play in encouraging the expansion of organic seed systems.

If you are an organic plant breeder, researcher, or student, we hope this report helps you understand emerging breeding and research priorities, both in the natural and social sciences, and that it aids you in identifying future funding opportunities for your work—and maybe even potential collaborators.

If you are an organic seed company, we hope this report helps you understand trends and perspectives related to organic seed sourcing, market needs and opportunities, and the way policy advocacy can support growth in the organic seed supply.

If you are an organic farmer, we hope this report underscores the importance of sourcing organic seed for the crops you grow to ensure strong integrity of the organic label and that the benefits of organic seed go beyond meeting a regulatory requirement.

If you are a policy maker, we hope this report clarifies the important role that seed systems play in the success of growers you serve—especially organic growers—and that decentralizing the highly consolidated and privatized seed industry is a social justice issue that can’t be ignored.

If you are a seed advocate, we hope this report provides the information and inspiration you need to take action to change seed systems—whether that’s informing your next seed purchasing decision or educating your policymakers about the benefits of organic seed.

How this report is organized

Chapter 1 covers the field of organic plant breeding by highlighting the common goals motivating these types of projects and the methods used. We also summarize plant breeding priorities by crop types as identified through our organic producer survey. We then share updated data on public investments in organic plant breeding and other organic seed initiatives, allowing us to report on progress seen since our last report in 2016. Through a survey of organic researchers, we are also able to identify outcomes, challenges, and ongoing needs from the perspective of grant-funded research programs, as well as these researchers’ opinions on various IPR strategies.

Chapter 2 discusses the needs of organic seed producers, including seed companies, by reporting on both production and non-production challenges identified through a national survey of seed producers/companies. This chapter reveals the growing impacts of climate change on seed producers, seed producers’ perspectives on IPR strategies, and how these producers define a resilient seed system. We also share how seed producer networks are currently structured, including who these producers collaborate with, where they source germplasm and production information from, and more.

Chapter 3 provides an overview of findings from our third organic producer survey. These findings help us understand how much organic seed producers are sourcing for their operations by crop type, where they source seed from, what factors impede organic seed sourcing, and the role that certifiers play in encouraging more organic seed usage. We also share takeaways from our certifier survey in this chapter to better understand certifiers’ perspectives and practices as they relate to enforcing the organic seed regulation.

Chapter 4 includes an overview of seed policy issues, beginning with an update on progress toward strengthening the organic seed regulation and clarifying excluded methods. Other policy areas covered include seed industry concentration, IPR tools and strategies, GMO contamination, and investments in public plant breeding. Organic seed stakeholders identified these policy issues as priorities through a policy survey we conducted in 2020.

Chapter 1: Organic Plant Breeding

Seeds are a living link to histories and futures, connecting us to a larger community. For centuries, seed saving allowed the genetic and cultural heritage of seeds to be passed on to the next generation, to travel great distances from centers of origin, and to adapt to different environments. In this way, the seeds that sustain us are only available because of the persistence of both plants and people, and their co-evolution.

Plant breeding is rooted in this long history of seed saving. Indeed, plant breeding and seed saving have always occurred together, alongside natural selection, and are responsible for the food crops we enjoy today. Farmers, gardeners, and seed savers the world over continue to conserve and improve crops through time-honored seed saving, sharing, and storage systems.

Plant breeding is widely recognized as a craft and science for developing or enhancing plant varieties. Different forms of modern-day plant breeding exist, ranging from lab-based methods operating at the cellular level to classical techniques applied through field-based selection of whole plants. While the two forms can complement each other, for purposes of this report, we mostly refer to plant breeding in the classical sense. With plant breeding comes a responsibility to carefully steward the world’s foundation of plant genetics, especially in the context of agriculture. It’s our responsibility to ensure future generations have the seed they need for their sustenance as well.

What is organic plant breeding?

Organic plant breeding is the practice of breeding plants in and for organic agriculture. Though still a burgeoning field, more farmers, universities, seed companies, and nonprofit organizations are embracing organic plant-breeding methods and goals. This is evidenced by the research investments described below, in addition to emerging studies that demonstrate effective methods and models for this area of practice. These studies show that organic plant-breeding projects are motivated by one or more of the following goals: (1) adapting seed to organic farming systems, (2) prioritizing traits important to organic growers and consumers, (3) increasing the organic seed supply, and (4) honoring the principles and values underpinning the organic movement, including equity and justice. These goals are further explored below.

Adapting seed to organic farming systems

Adapting plant genetics to specific regions and growing practices is an effective strategy for strengthening climate resilience—both on the farm and for the broader seed and food system. Organic plant breeding embraces selection under organic conditions over the course of several generations. Studies show the benefits of breeding crops in the environment of their intended use, including evidence that conventionally bred varieties don’t always perform as well under organic and low-input conditions.

While there are overlaps in breeding goals for conventional and organic production, such as improving yields and disease resistance, priorities are often different because the farming practices and inputs are different. For example, conventional systems can compensate for a plant variety lacking important traits (e.g., nitrogen-use efficiency) through inputs prohibited in organic systems (e.g., synthetic nitrogen fertilizer). In this way, conventionally bred varieties can rely on synthetic inputs for their success. Ideally, varieties bred for organic systems have intrinsic traits that benefit from a whole-systems approach to pest, disease, and nutrient management. This distinction dictates organic plant-breeding priorities in addition to other needs informed by the targeted region, market, and culture.

We are having to use varieties and species that have been bred to perform differently. Some crops in the field…just seem to compete better with weeds than others, so they compete better with some of our organic practices. And so that tells me that if we had some breeding programs for selecting around organic production practices we could make a lot of headway.”

Organic producer

Prioritizing traits important to organic growers and consumers

Organic farmers understand the benefits of organic plant breeding. Most of the producers (86 percent) who responded to our national survey (discussed in Chapter 3) believe that varieties bred for organic production are important to the overall success of organic agriculture. Organic crop researchers play an important role in meeting these needs. Our nationwide research survey (discussed later in this chapter) finds that organic crop research agendas generally align with the needs of organic growers. This is evidenced by survey results that communicate the needs and priorities for organic plant breeding (see“Organic plant breeding priorities reported by growers and researchers”).

Organic plant breeding priorities reported by growers and researchers

Organic producers were asked which crops are most in need of improvement and which traits should be prioritized. They reported the following organic plant-breeding priorities by crop type. Crops and traits are listed in order of identified importance.

- Field crops:

- Corn (yield, competitiveness with weeds, and nutrient-use efficiency)

- Soy (competitiveness with weeds, germination/seedling vigor, and yield)

- Wheat (yield, quality, and nutrient-use efficiency)

- Vegetables:

- Tomatoes (disease resistance/tolerance, flavor, and quality)

- Brassicas (disease resistance/tolerance, heat tolerance, and yield)

- Cucurbits (disease resistance/tolerance, yield, and heat tolerance)

These results are similar to our 2011 and 2016 report findings, although interest in heat-tolerance in brassicas and cucurbits is new.

Organic plant breeders and other researchers were provided the same list of crop traits as organic producers to score the importance of these characteristics for the crop types that they work with. They identified the following characteristics as most important for their work:

- Vegetables (disease resistance, flavor, and germination/seedling vigor)

- Field crops, small grains, and pulses (disease resistance, yield, and abiotic stress resistance)

- Forage and cover crops (yield, cold-hardiness/season extension, abiotic stress resistance

Research by the Hartman Group, a market analysis firm, provides insight into the organic market, including consumer attitudes and behaviors surrounding the organic landscape. Their most recent study, “Organic and Beyond 2020,” concluded that perceptions of health and safety are the top reasons consumers choose to purchase organic food. Many consumers also identified organic to be a marker of a quality product that tastes better and fulfills nutritional needs. Unsurprisingly, these consumer preferences show up as organic plant-breeding priorities, where flavor and nutritional content are components of many breeding-project goals and evaluations.

Increasing the organic seed supply

Organic plant breeding and organic seed production are interrelated but distinct activities. Most organic seeds on the market were bred in and for conventional farming systems, and then the seed crops were grown organically. For seeds to be certified organic, they must be produced in accordance with the organic regulations and on land certified by an accredited certifying agency. The organic regulations don’t certify plant breeding practices other than clearly defining which methods (e.g., genetic engineering) are excluded and which substances (e.g., chemical seed treatments) are prohibited.

As will be discussed in the next chapter, most organic producers still rely on conventional seed for at least part (if not all) of their operation. Our data shows very little progress in increased organic seed sourcing except for some vegetable producers. Organic plant breeding can help to fill supply gaps as organic seed production increases.

Honoring the principles and values underpinning organic agriculture

As organic plant breeding expands as an area of science and as a collaborative space, breeders have an opportunity to define organic breeding not by what it excludes—such as GMOs and synthetic pesticides—but by what it embraces. Breeding principles and methods have come into sharp relief in the context of excluded methods as defined by the NOP (see the excluded methods discussion in Chapter 4). The principles described in the introduction can serve as a touchstone for ensuring that organic plant-breeding practices and philosophies support the development of decentralized and democratic seed systems. These principles are connected to those established by IFOAM in important ways: the principles of care (abiding by the precautionary principle); ecology (preserving and applying biodiversity); fairness (promoting equity and justice); and health (honoring the interrelationship of soil, plants, animals, and humans).

Many organic plant breeders work to incorporate desired traits from older varieties—such as flavor and color—into modern varieties that express other useful traits, such as high yield. In this way, these “heirlooms of tomorrow” are adapted to modern environments and climates and include characteristics important to both growers and consumers (see “Heirlooms of tomorrow”). The conservation of crop genetic diversity—and adapting this diversity to changing climates, resource availability (such as water), and food production needs—is often emphasized in many organic plant-breeding projects.

We believe the broader goals of organic plant breeding can include preserving biodiversity, supporting healthy ecosystems, growing healthy food, and protecting farmers’ rights to save seed and achieve seed autonomy. Increasingly, these values encompass an understanding of a crop variety’s origin and appropriately acknowledging and compensating original stewards. Just as plants have intrinsic value, so does the seed knowledge that accompanies this co-evolution.

Heirlooms of tomorrow

Edmund Frost of Common Wealth Seeds has spent more than a decade crossing traditional and modern varieties of winter squash to achieve varieties with exceptional disease resistance, eating quality, and storage life. Most recently, Frost conducted selections from an earlier cross he made between Seminole pumpkin and Waltham butternut, an outcome he calls “South Anna,” named after a river near his residence in Louisa, Virginia. Frost has crossed South Anna with other varieties from both tropical and temperate climates, including a Guatemalan Ayote squash that often exhibits green flesh and a variety bred by Johnny’s Selected Seeds called JWS 6823. The varieties resulting from Frost’s crosses and selections are gaining popularity among butternut squash growers. Ultimately, Frost plans to have a few different varieties available that offer growers good downy mildew resistance, more uniformity, and diverse sizes and flavor profiles.

Another example includes the late Jonathan Spero, a farmer-breeder known for his commitment to developing open-pollinated sweet corn that combined older landrace varieties with more popular modern varieties. He believed that growers should be able to save and adapt their own seed, and this was particularly true in his work with sweet corn. His goal was to develop open-pollinated varieties with good yield and sweetness to serve as alternatives to the dominant hybrids in the market. Spero selected for flavor, robust growth, and multiple ears per plant, but he also aimed to preserve genetic diversity to allow for adaptability. Jonathan left this world too soon in 2020, but his legacy lives on in the form of several “heirlooms of tomorrow” varieties of sweet corn (Tuxana, Top Hat, Zanadoo, Aloha #9, Festivity, and Anasazi Sweet); lettuce (Emerald Fan); broccoli (Solstice); and sugar beet (Nesvizhskaya).

Collaboration and decentralization as key strategies

Collaboration has emerged as the process often best suited to achieve the goals described above. These goals require that breeders engage with the unique needs of organic farmers in their region, pool resources for growing out seed, and involve different bases of knowledge and experiences to navigate the tension between diversity and uniformity. In particular, participatory plant breeding is a common model used in organic breeding projects. This approach involves farmers, formal plant breeders, and other stakeholders—such as seed companies and chefs—working together to set breeding priorities and to evaluate the results from both a producer and consumer perspective. By combining the practical experience of farmers, the food industry, seed companies, and formal plant breeders, these collaborations result in more organic seed with traits that are useful to organic growers—and with more growers who possess the skills to develop or improve their own varieties.

This participatory model lends itself to a decentralized approach to improving the foundation of our food system. The emergence of organic plant breeding and participatory models are in part a response to consolidation in the seed industry, where the private sector does not fulfill all the seed needs of growers—especially organic growers. Market concentration and the increased privatization of seeds have narrowed crop genetic diversity in our fields and resulted in an overemphasis on breeding for major crops and large-scale agriculture. For example, most major crops—corn, soybeans, canola, cotton, and sugar beets—are genetically engineered to be resistant to a handful of herbicides and pests.

Organic agriculture is a system based on biodiversity. In the face of market consolidation, the diversity of plant breeders, breeding approaches, and stewards of our seed collections is more important than ever. Participatory models can serve as a complement to profit-driven breeding programs, and involving farmers is increasingly understood as an effective and efficient strategy for conserving crop genetic diversity and developing varieties of use to growers.

Public investments in organic plant breeding and organic seed

While we don’t have data on seed company investments in organic plant breeding, we have analyzed, for a third time, public research investments going toward organic plant breeding and other organic seed initiatives. Our findings show similar investment trends to our last report, with some notable distinctions—including a significant increase in the amount of funding.

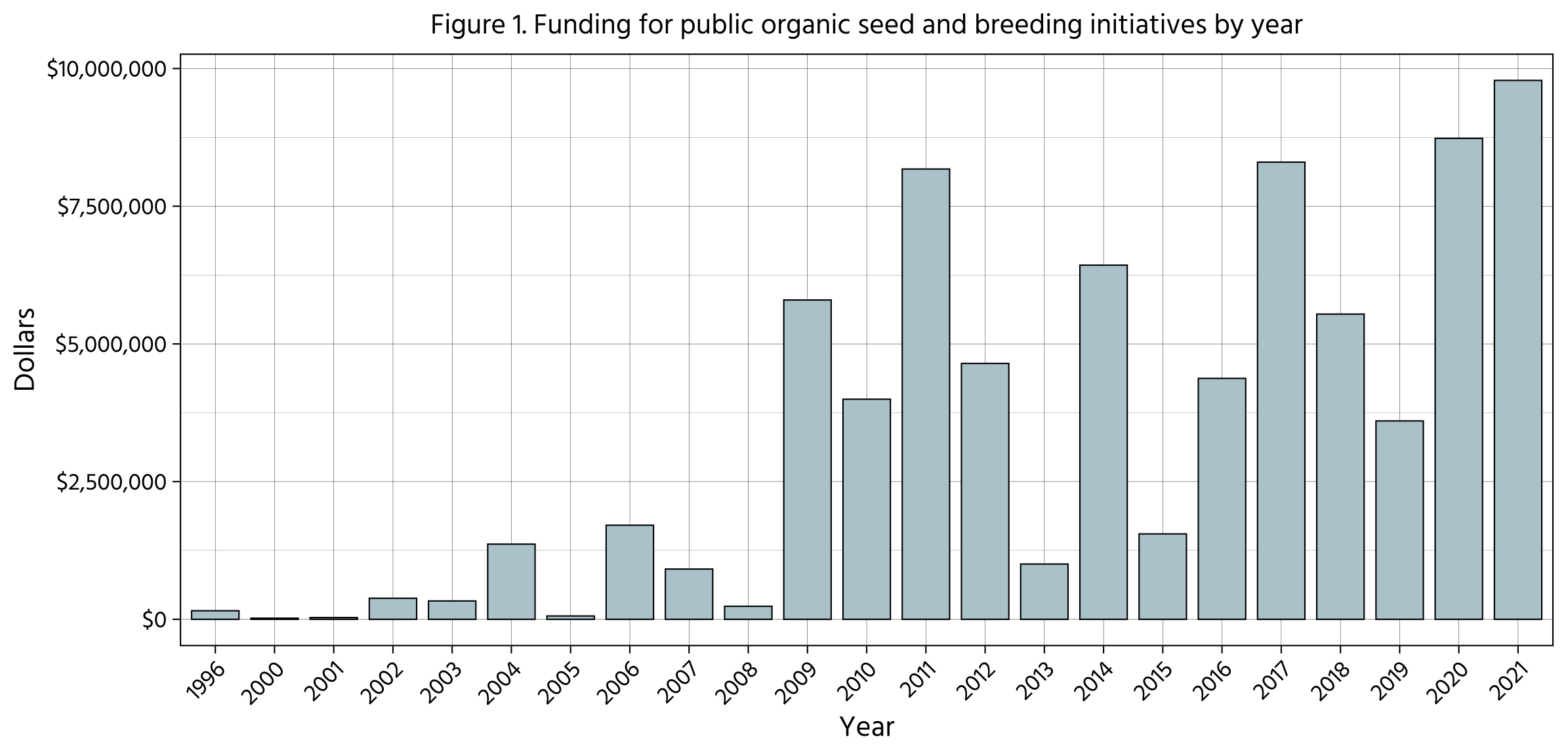

In the last five years, there has been more than $39.8 million in public investment for organic plant breeding and other organic seed initiatives.

In the last five years, there has been more than $39.8 million in public investment for organic plant breeding and other organic seed initiatives. This represents the largest public investment in organic seed systems we’ve recorded (see Figure 1). These investments by state and federal agencies, and a handful of private foundations, are certainly something to celebrate. We view this growth as evidence that more researchers—and the granting agencies and foundations supporting them—understand that these investments are paramount to the development of organic seed systems and the growers and communities who rely on them.

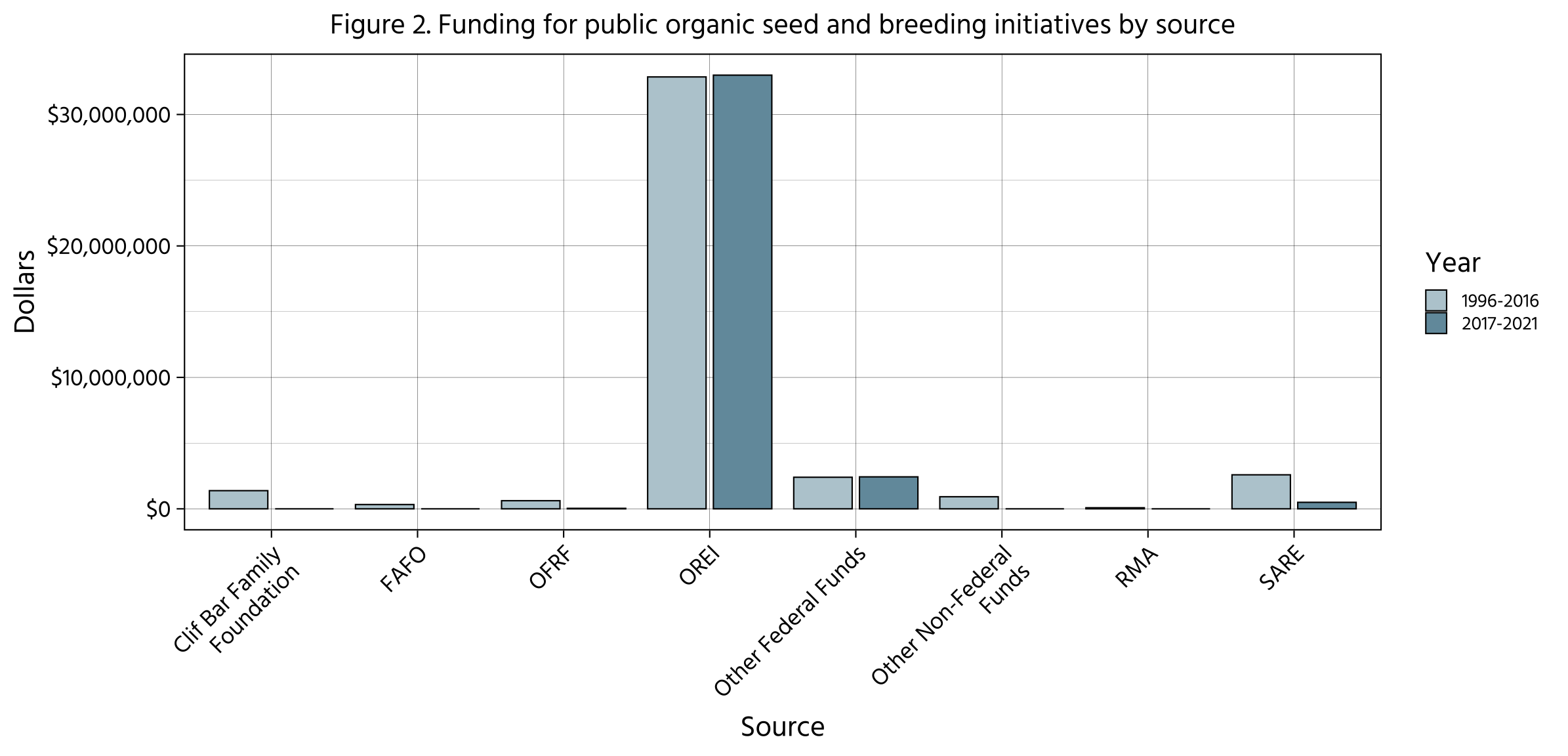

Most funding for organic plant breeding and other organic seed initiatives continues to come from the USDA’s Organic Agriculture Research and Extension Initiative (OREI), representing 92 percent of investments over the last five years (see Figure 2). Collectively, since we started tracking these investments, OREI represents 85 percent of all funding that has gone toward these areas of research. Other major sources of federal funding include the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program and other federal programs, including USDA’s Risk Management Agency, Rural Business Development Grants, Specialty Crop Block Grants, Hatch funds, and others.

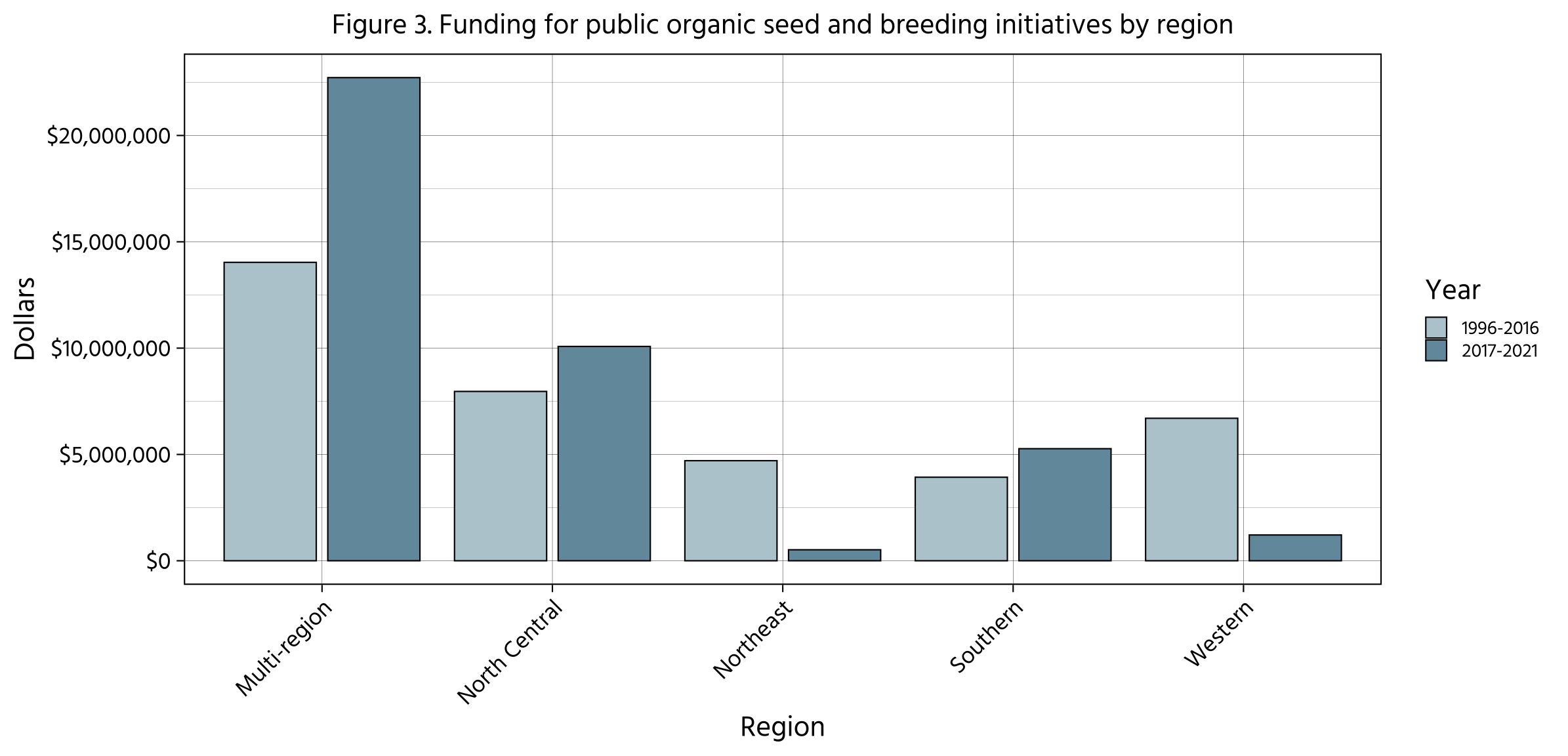

Many of the funding trends and priorities are the same or very similar to those reported in past reports. By region, projects labeled as “multi-regional” received the most support, followed by projects located in the North Central, Southern, Western, and Northeastern regions, respectively (see Figure 3). This finding underscores the collaborative nature of many organic plant-breeding projects, as mentioned above, where the number of multi-state and multi-stakeholder projects continues to increase.

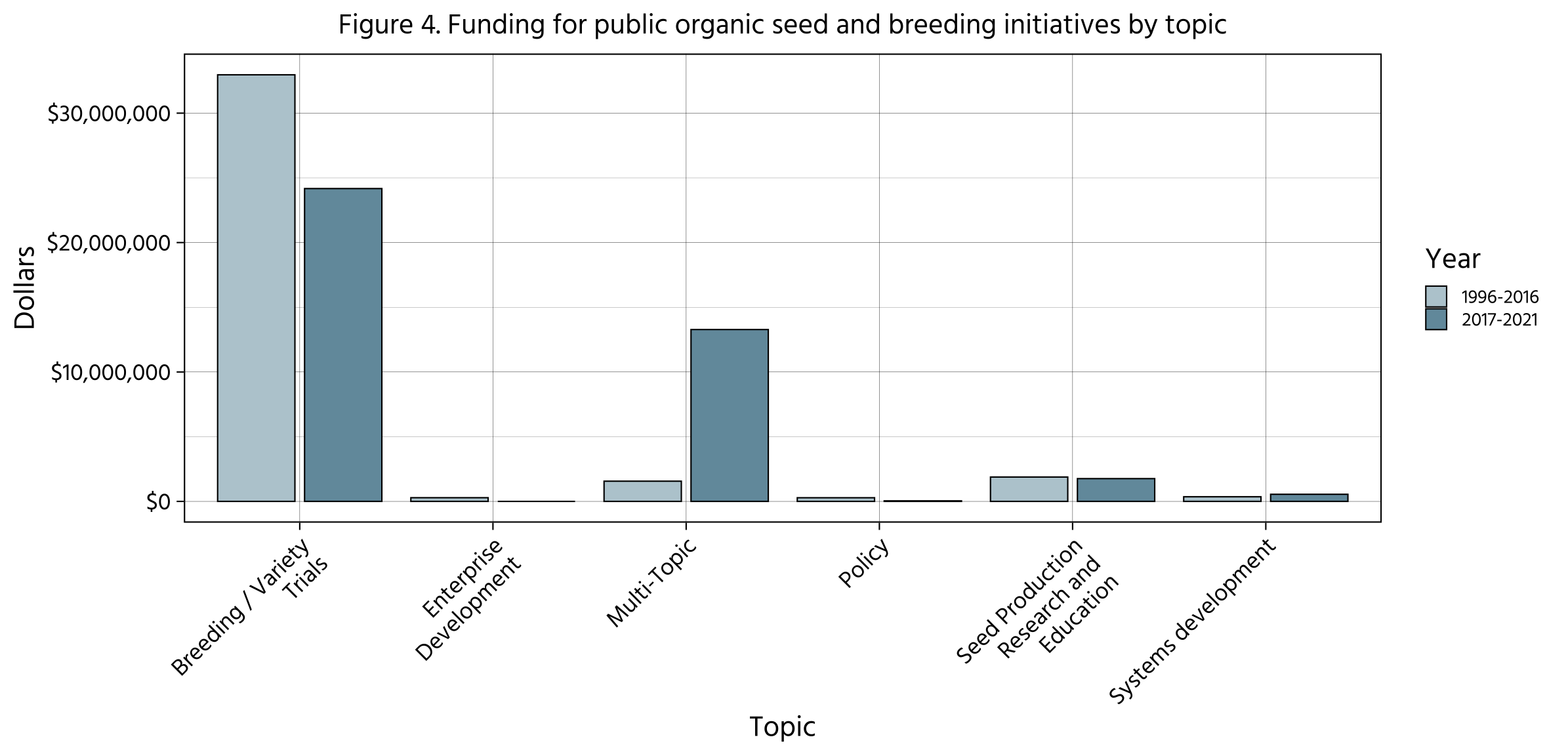

We also saw similarities to our 2016 report in respect to which topics received funding. Once again, plant-breeding and variety-trial projects received the most funding, followed by multi-topic projects and seed production research and education (see Figure 4). Over the last 25 years, only 5 percent of these research dollars have gone toward organic seed research and education.

Most organic breeders are located in New England, Northern Europe, or the Pacific Northwest. As such, their varieties tout frost resistance but almost none are bred for the South. This is a significant and growing problem each year as the climate warms.”

Organic Producer

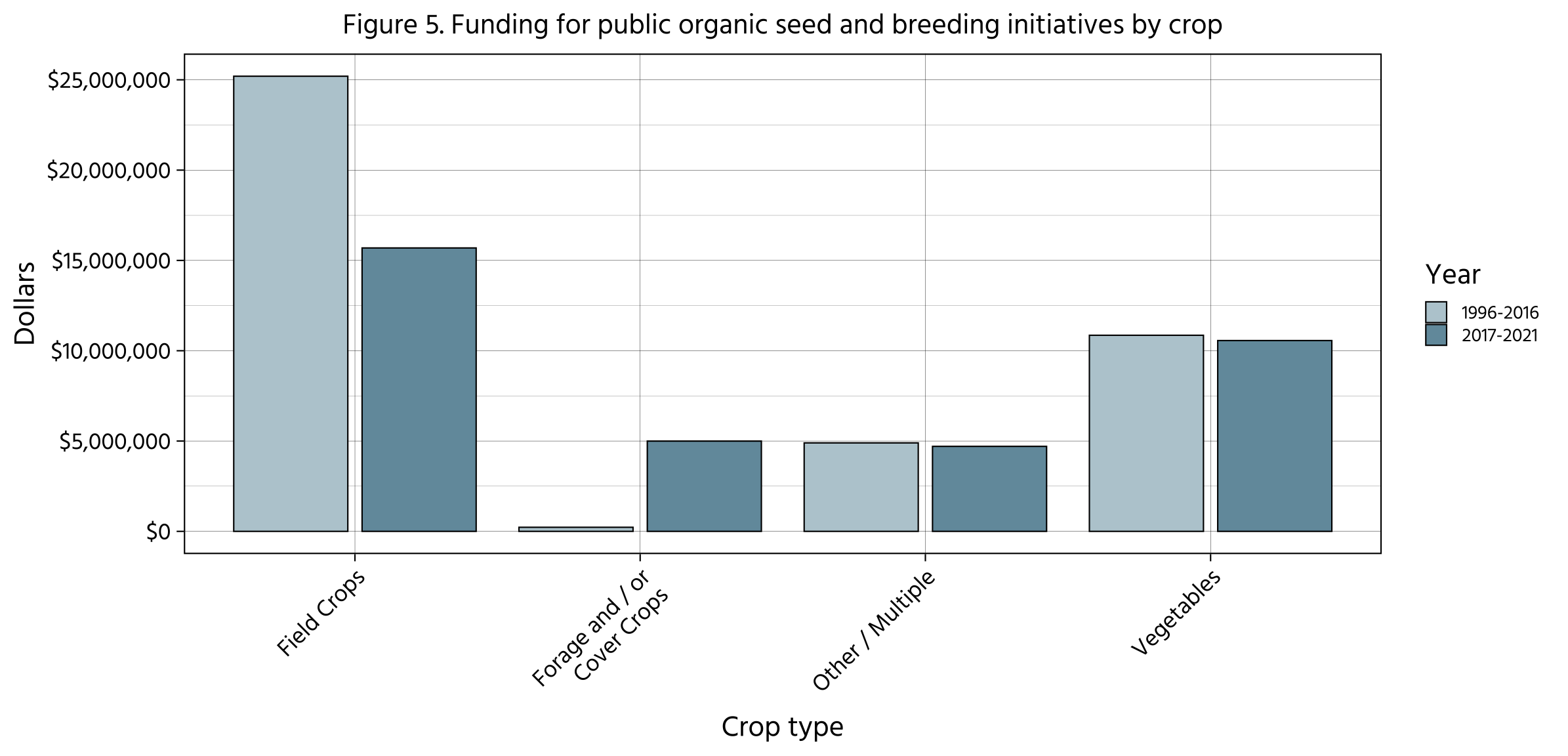

By crop type, vegetable and field-crop projects received the largest amount of support (see Figure 5). After receiving very little support in the past, forage and cover crops have seen increased investments in the last five years.

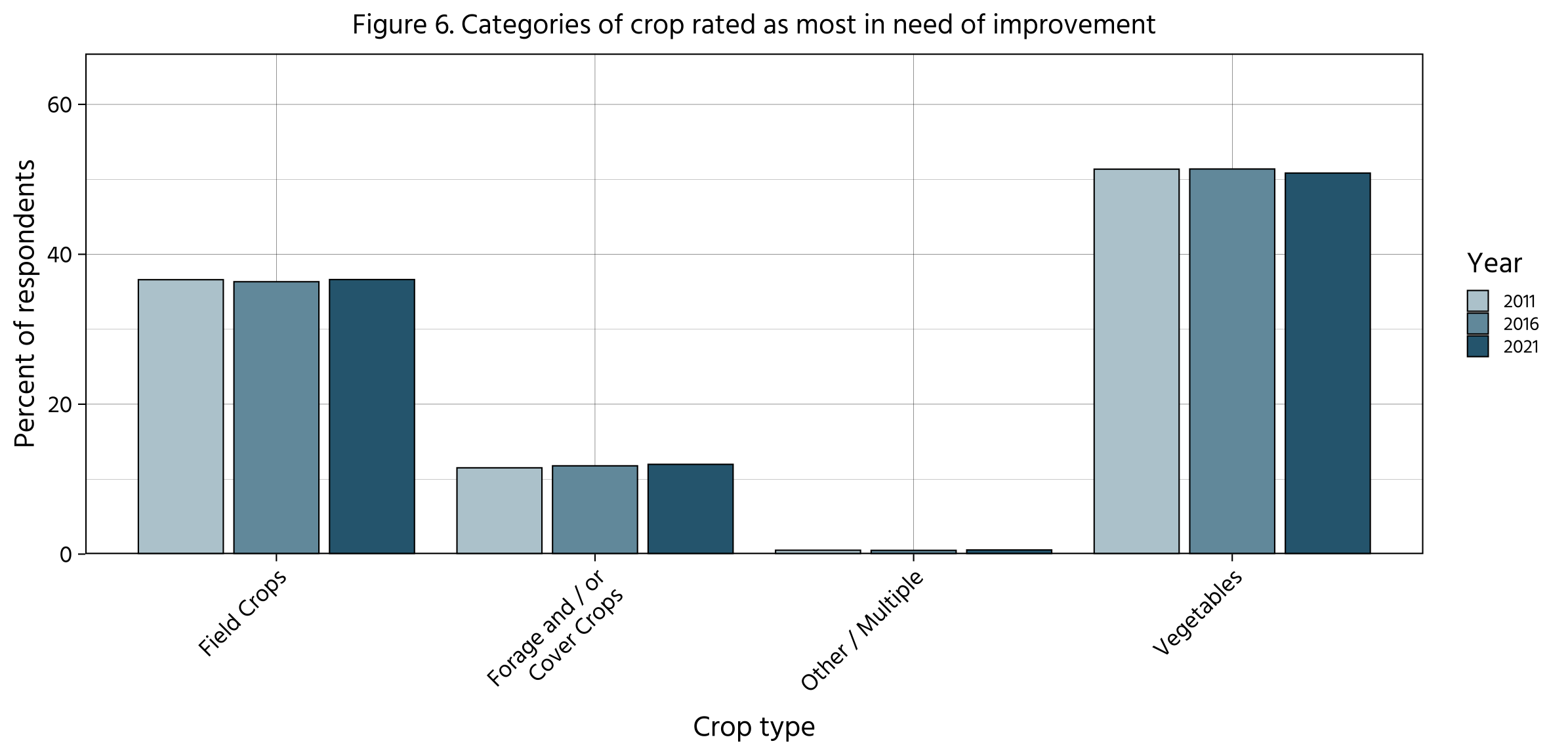

In our organic producer survey (further explored in Chapter 3), we asked which crops were most in need of improvement for organic agriculture. When combining the result from this question with those from the same question in previous reports, we found that about 51 percent of respondents indicated vegetable crops, 36–37 percent field crops, 12 percent forage or cover crops, and 1 percent multiple categories (see Figure 6). Comparing the funding by crop category to the categories of crops in need of breeding, vegetable crops were the category where most producers indicated a need for breeding, while field crops received the most funding.

Are current research investments equitable?

As explained above, the OREI program is currently the largest source of funding for organic plant breeding and other organic seed research investments. The 2018 Farm Bill more than doubled funding for this program, and soon OREI will award $50 million in grants annually. Given its size, the OREI program tends to award larger sums of money compared to other programs that support organic research.

This means that financial resources tend to get funneled toward larger research programs, usually at the leading land grant universities, which have staff capacity to manage government grants and the tedious paperwork and reporting that come with them. The burden of paperwork per project partner can also disincentivize paid collaboration with broader groups of stakeholders. We view this as an access and equity issue for research programs—especially smaller university programs and non-university institutions (e.g., non-profit research)—and a barrier to increasing the diversity of grant recipients and partners, especially those who lack the capacity and experience necessary to apply for and manage large grants.

Given that racism is embedded in food and agriculture, and in our institutions and agencies, there is a strong need to connect plant breeding and other research priorities to social movements, with the goal of influencing seed systems and the broader food system through a justice lens.

To be sure, public plant-breeding programs at land grant universities are serving important needs not fulfilled by the private sector, and many are severely underfunded. At the same time, Indigenous communities and other marginalized groups have endured many injustices committed by both land grant institutions and the USDA. This is a sordid history that organic plant breeders and researchers, and the funders supporting them, must reckon with if organic seed systems are to support a diversity of growers, researchers, and seed companies and to avoid perpetuating institutional racism. Given that racism is embedded in food and agriculture, and in our institutions and agencies, there is a strong need to connect plant breeding and other research priorities to social movements, with the goal of influencing seed systems and the broader food system through a justice lens.

As will be discussed in Chapter 4, organic research is already underfunded, and relying heavily on one funding source to advance organic plant breeding and seed research perpetuates a funding model that may only benefit a limited number of stakeholder groups while abandoning others. Overreliance on one program also makes organic plant breeders and other researchers—and the growers they serve—vulnerable to unpredictable delays or funding gaps caused by Congress. For example, the OREI program is reauthorized in the Farm Bill every four to five years. In 2012, due to infighting, Congress didn’t pass a Farm Bill before the OREI program expired, resulting in organic research losing an entire year of funding in 2013.

As investments increase, what results are we seeing?

In 2021, OSA conducted a survey of principal investigators listed on grant-funded projects and recent publications that focused on organic plant breeding and/or organic seed to better understand the outcomes of recent research investments. Fifty-one researchers responded to the survey, which asked questions related to their areas of research (expertise and crop priorities); project successes, challenges, and future needs; perspectives on intellectual property rights and climate change; and more. The full dataset can be explored here:

https://organicseed.shinyapps.io/SOSData

Who took our researcher survey?

Researchers in our survey include principal investigators from both universities and organizations across the country. The response rate for this survey was 61 percent (51 out of 83).

- Where are they from? The researchers surveyed come from 23 different states, representing universities (84 percent of responses) and organizations (16 percent).

- What are their expertise? The university researchers come from multiple disciplines. About half identify as breeders and a third as agronomists, geneticists, and/or horticulturalists. Less represented are soil scientists, ecologists, weed scientists, plant pathologists, and social scientists. Organization researchers specialize primarily in research and education but also in advocacy, technical support to farmers, breeding, and community development.

- What crops do they work with? Of the multiple crops the researchers work with, 45 percent work with vegetables, 40 percent with field crops, 32 percent with small grains, and 23 percent with forage crops.

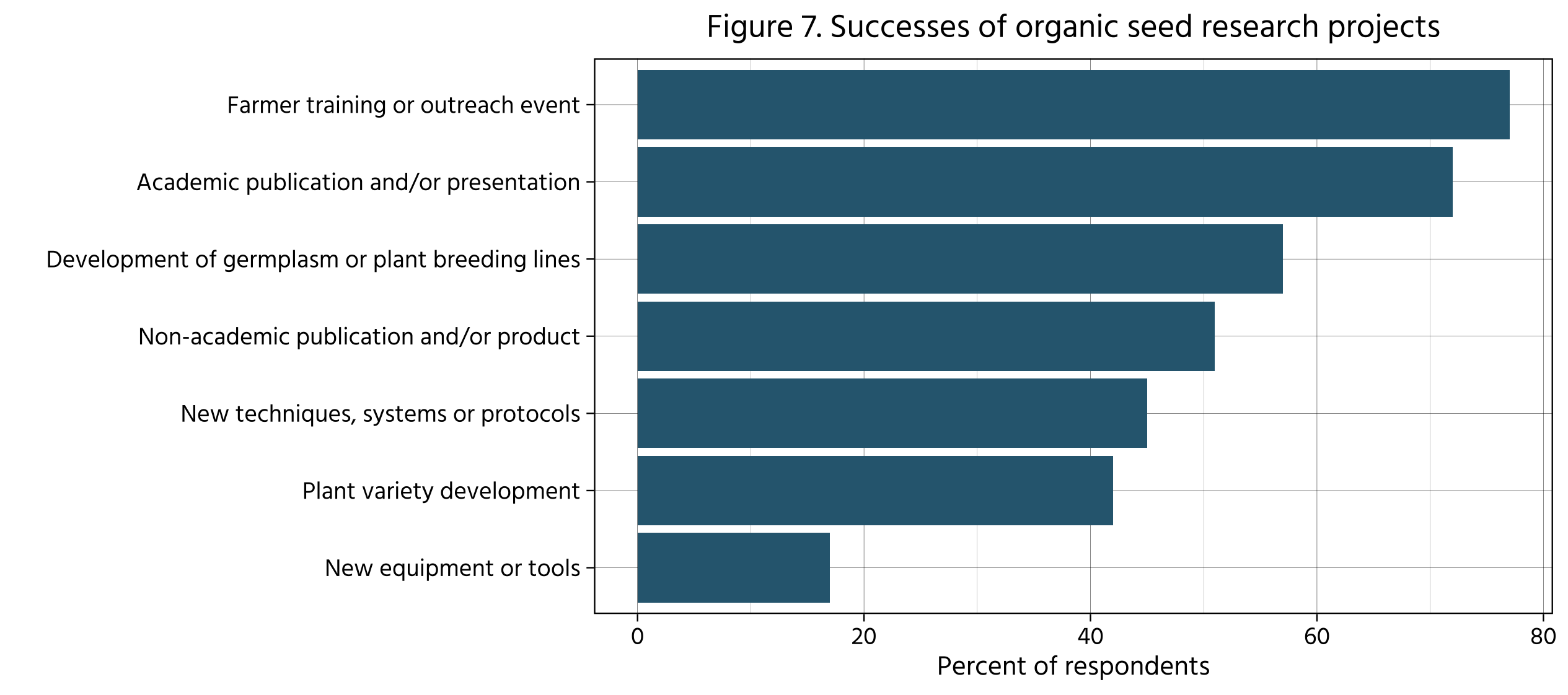

The most common uses of public research funds, according to the researchers surveyed, included farmer trainings and outreach events (76 percent of respondents) and academic publication and/or presentations (75 percent). Researchers also reported the development or identification of germplasm or plant breeding lines as an outcome (57 percent) as well as plant variety development (41 percent) (see Figure 7).

Researchers who identified plant variety development as a project outcome were also asked if any finished varieties or breeding material were released as part of their most recent project. Of these researchers, 40 percent said they finished a variety or released breeding material. This rate is up from 2016, when 30 percent of researchers reported releasing finished varieties. To protect the material they released, most researchers (53 percent) used Material Transfer Agreements, while other IPR strategies included Plant Variety Protection (24 percent), the Open Source Seed Initiative (OSSI) pledge (12 percent), utility patents (6 percent), and licenses (6 percent).

These researchers were also asked if they were able to use earned revenue from variety releases or technology licenses to help fund their most recent project. Forty-two percent of the researchers said they were able to use earned revenue to support their project, which is up from only 15 percent in 2016.

This survey also captured researchers’ perspectives on IPR strategies (see Table 1). Researchers were asked how they would describe the impact of different IPR on organic seed systems, ranging from “very harmful” to “very helpful” (see Figure 8). The protections identified as “very helpful” and “somewhat helpful” were the OSSI pledge (62 percent), Material Transfer Agreements (58 percent), and Plant Variety Protection (48 percent), while only 22 percent of responses considered utility patents helpful.

Interestingly, there is a large difference between researchers’ widely perceived helpfulness of the OSSI pledge and their limited use of the pledge to protect newly released materials. This difference suggests that researchers’ support for the OSSI pledge may not be shared by university technology transfer offices. The reason for that may lie in this plant breeder’s remark: “My uncertainty about OSSI stems from the fact that it does not have a mechanism for the breeder to be compensated.” Alternatively, some grant-funded researchers may support OSSI because they don’t have to rely on royalties for the continued viability of their program.

| Material Transfer Agreement | Used widely in the seed trade between seed developers, farmers and developers, and others. Contracts are binding between the signatories, but the materials are often associated with one of the other forms of IP. Contracts between universities (e.g., Material Transfer Agreements) are typically used to support research, while those used by industry typically restrict research. |

| Plant Variety Protection (PVP) | PVP certificates are awarded to plant developers who can demonstrate their variety is new, unique, uniform, and stable. PVPs give developers exclusive marketing rights, but the Plant Variety Protection Act governing this program explicitly allows PVP varieties to be used for research and breeding purposes and allows growers to save PVP varieties for on-farm use (i.e., a grower can’t sell PVP seed). PVPs last twenty years and then these varieties enter the public domain. |

| Utility Patent | Utility patents are available through the US Patent and Trademark Office for inventions that are novel, non-obvious, and useful. They have been awarded for finished varieties, plant parts, genetic traits, and more. Utility patents apply to all users regardless of how they obtain the material. Utility patents last twenty years and can be enforced to restrict seed saving, research, breeding, and more. |

| Open Source Seed Initiative Pledge | An OSSI pledge covers varieties that aren’t protected by another form of IP rights. Plant breeders must submit an application to the OSSI Variety Review Committee to earn approval for using the OSSI seal and pledge, which states: “You have the freedom to use these OSSI-pledged seeds in any way you choose. In return, you pledge not to restrict others’ use of the seeds…and to include this Pledge with any transfer of these seeds or their derivatives.” |

Table 1. Intellectual property tools and strategies included in surveys

Researchers reported a number of obstacles in meeting the goals of their projects. The biggest obstacle reported was limited time and/or staff capacity (61 percent), followed by delays or alterations due to COVID-19 (55 percent), unexpected environmental conditions (49 percent), and insufficient funding (43 percent). As one researcher shared, “We essentially lost a whole season of seed harvesting and data collection for multiple crops due to quarantine and suspension of research operations due to COVID-19.”

We essentially lost a whole season of seed harvesting and data collection for multiple crops due to quarantine and suspension of research operations due to COVID-19.”

Dr. Hector Pérez, University of Florida

Challenges related to weather and environmental conditions ranged from “heat stress” and “extreme heat” to a “very rainy fall that led to high disease pressure” and “freezing temperatures inside high tunnels.” The need for reliable and longer-term funding was a theme in survey responses, both within and outside federal grants. “We chase money,” one researcher said, “but don’t finish much.”

Takeaways

- Organic plant breeding is an expanding field that is making progress toward a number of goals: adapting seed to organic farming systems, prioritizing traits important to organic growers, and elevating the principles that underpin the organic movement. In support of these goals, collaboration and decentralization are key strategies in organic plant-breeding projects.

- Organic plant-breeding projects pursued by researchers generally align with the needs of organic producers, where vegetables and field crops are the most popular crop categories being researched and disease resistance and yield take priority.

- Organic research investments are increasing, the bulk of which come from USDA OREI and are dedicated to breeding and variety trials. Of the USDA SARE-funded programs, multi-regional work receives the most funding, as researchers across the country collaborate to support organic research.

- As investments in organic plant breeding and organic seed increase, the organic principles are a necessary touchstone for ensuring that seed systems embrace diversity, health, and fairness as they grow alongside the success of the broader organic industry.

- Organic researchers are having greater success developing new varieties, which are most often protected by Material Transfer Agreements, and supporting their projects through earned revenue, compared to previous reports. However, challenges remain regarding staffing and capacity for researchers to carry out their projects.

Chapter 2: Organic Seed Production

Seed growers are at the heart of organic seed systems. From farmers who save seeds to the growers behind the varieties in seed catalogs, there wouldn’t be a seed—or food—supply without these producers. By the very nature of their work, seed growers continue the time-honored practice of keeping our seeds alive and adapting to changing environmental conditions and needs. The challenges posed by climate change and seed-industry consolidation underscore the importance of centering seed growers in strategies that enhance the resiliency and sustainability of our food and farming systems.

In many communities, the local food movement has been successful in revealing the faces and stories behind the meals on our plates. We see this movement now evolving to uplift the seed growers behind our food. Uncovering the story behind our seeds allows us to reconnect with the foundation of our food system and to see more clearly the challenges and opportunities for creating organic seed systems that are diverse, resilient, responsive, and just.

To uncover the story behind the commercial seed system is to reveal a tremendous amount of industry consolidation: four companies control more than 60 percent of the global commercial market. This troubling statistic has brought more public attention to where and how seeds are grown and by whom—and to the question, “Who ‘owns’ seeds anyway?”

Exposing the consequences of consolidation—less genetic diversity, fewer options in the marketplace, and higher prices—has spurred a resurgence in local seed conservation and exchange efforts, as evidenced by the hundreds of seed libraries that have popped up over the last decade here in the US and across the globe. New seed companies have also emerged in response to consolidation. These are mostly small, regional enterprises focused on protecting and expanding genetic diversity, developing varieties for organic and low-input farms and gardens, and offering culinary and nutritional characteristics desired by organic consumers.

Growing seed crops requires different skills, knowledge, and equipment than growing crops for food, so targeted investments of time, resources, research, and shared learning are needed to support those interested in growing seed or expanding their seed enterprises. As we just learned in Chapter 1, though organic research funding is expanding, only 5 percent of that funding went toward organic seed production research and education. Yet, nearly 40 percent of organic farmers who responded to our national survey say they’re interested in producing seed commercially.

Understanding the needs of organic seed growers and companies

Fewer organic producers report saving their own seed or producing seed on their farm compared to five years ago.

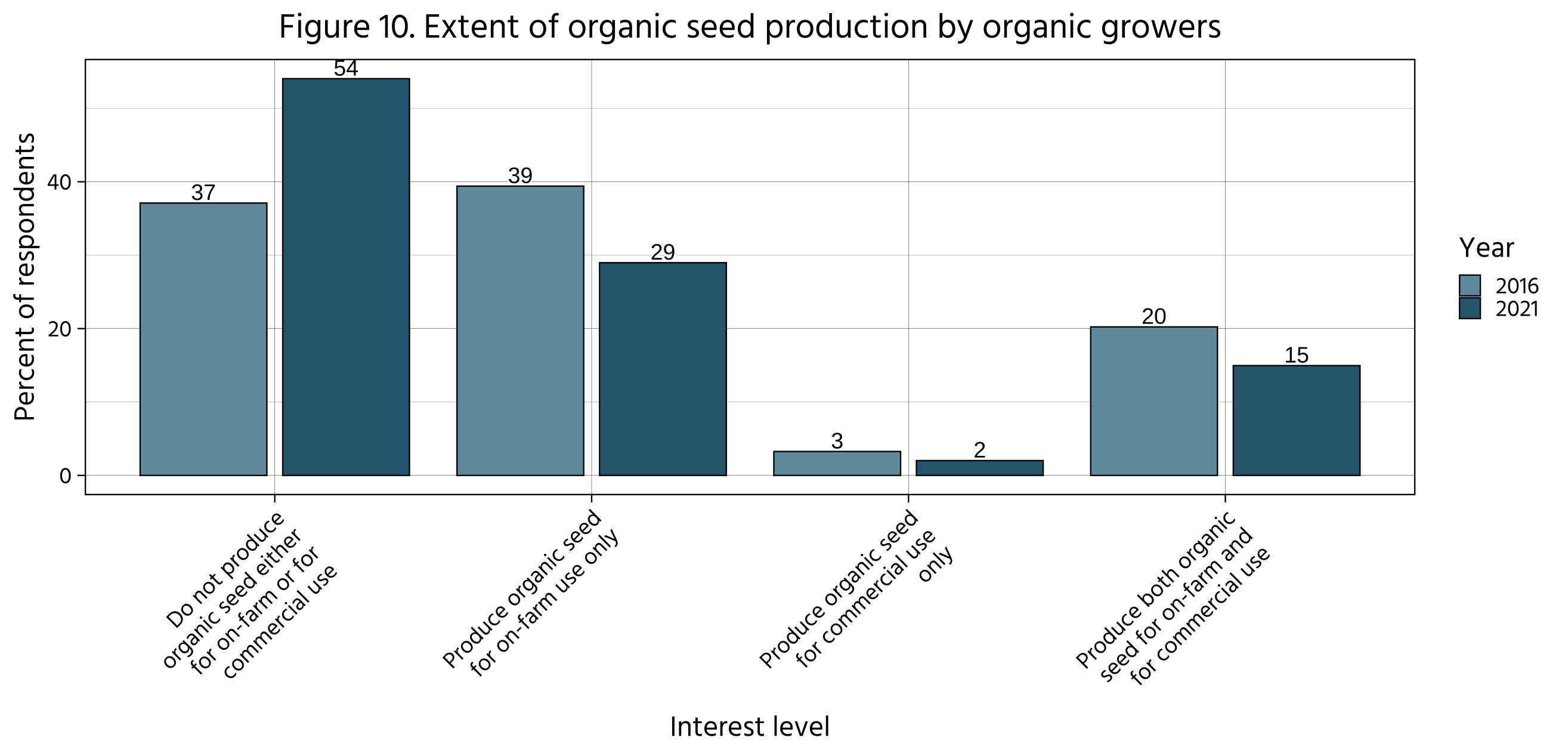

Over the years, State of Organic Seed has documented interest among organic crop growers in producing organic seed, and in past reports we found a growing percentage of organic farmers using their own saved seed. In 2011, 39 percent of growers who responded to our organic producer survey (not to be confused with our organic seed producer survey) said they were using seed grown on their farm, and in 2016 this number grew to 43 percent of respondents. In 2021 we found this number to be much lower, with 25 percent of respondents saying they used seed that they had saved (see Figure 9). In 2016, 63 percent of respondents to this same survey said they were producing seed for on-farm use or to sell commercially. This number dropped to 46 percent in 2021 (see Figure 10).

The challenges growers face when saving or producing seed may figure prominently in the decision about whether to grow seed or not. As you’ll read in this chapter, challenges loom large for growers who choose to produce seed, but a number of additional reasons factor into a grower’s decision to integrate seed production into their farming operation—reasons that go beyond seed production challenges. Some of the reasons growers might choose not to grow seed crops one year (or ever) include higher input costs, labor challenges, too many crops and not enough time, the need to focus on crops with the highest profit margin, and more.

We would like to start selling organic seed but are unclear on how to do this starting on a small scale.”

Organic Producer

In 2021, we conducted a survey and interviews with certified organic seed producers to better understand their challenges. We distributed the survey to 416 seed producers from the National Organic Program’s list of certified operations and to 90 organic seed companies. The full dataset, which represents 127 responses, can be explored at this link: https://organicseed.shinyapps.io/SOSData.

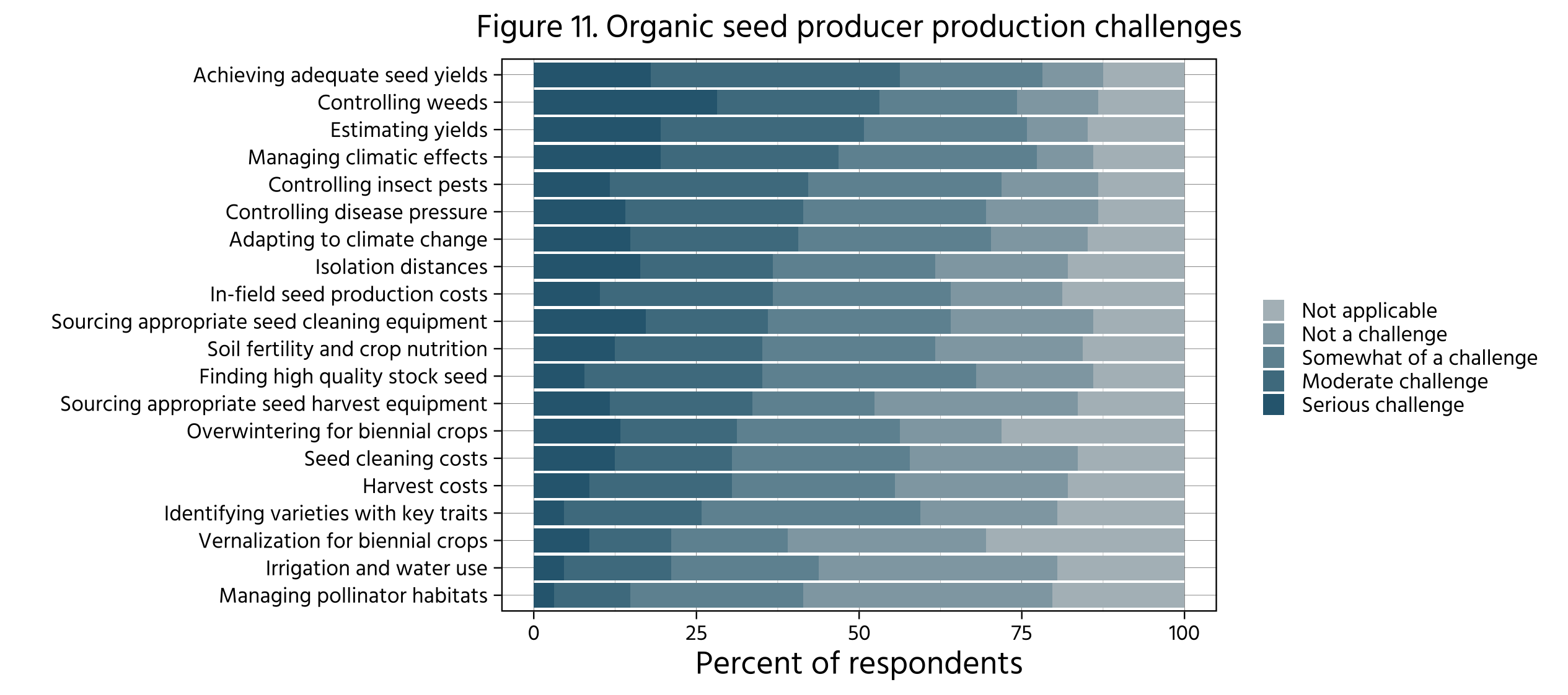

Our survey asked seed producers to rate the seriousness of challenges they face. We divided these challenges into two categories: (1) those related directly to production and field management (“production” challenges — see Figure 11) and (2) those that relate more broadly to social, economic, and policy issues (“non-production” challenges — see Figure 12). The greatest challenges that seed producers identified are described below.

Who took our seed producer survey?

Seed producers take on multiple roles in the seed supply chain. In addition to growing seed, these producers may also breed, process, and retail seed. As a result, we use the phrase “seed producer” interchangeably with seed growers and companies. The survey response rate was 25 percent (127 out of 506).

- What roles do they take on? Those who completed the survey represent these activities at the following rates: seed production (93 percent), seed retail (52 percent), breeding (45 percent), seed handling and/or processing (28 percent).

- Where are they from? The seed producers surveyed came from 31 states and three Canadian provinces. Representation in the US was similar for all USDA SARE regions except for the North Central region, which had proportionally fewer respondents.

- What crops do they work with? While many respondents grew more than one category of crop, most respondents work with vegetable seeds (77 percent) followed by ornamental seeds (including annual flowers and perennials—52 percent), with about a third of respondents growing seeds for field crops (31 percent), forage crops (33 percent), grain (37 percent), and propagules (35 percent).

- Operation and experience details? Respondents reported a wide range of incomes, with the plurality (29 percent) grossing less than $50,000. The average number of years of experience with farming was 19.5, and the average number of years of experience with seed production was 10.

Seed Production Challenges

Achieving and estimating adequate seed yields: Being able to estimate and achieve yields is critical for production planning and profitability. Achieving adequate seed yields was the top challenge reported by seed producers (78 percent of respondents—Figure 11) and estimating yields was similarly high (77 percent). To address the challenge of achieving adequate yields, producers need better ways of improving soil fertility to benefit their crops, without aiding the competing weeds and pests. Respondents explained that the challenge of estimating yield is due to an information deficit, and they provided ideas for filling this need, including “a database of expected yield ranges and market price ranges” and “regional data gathering” on crops and specific varieties.

Controlling weeds: Weed control is a common challenge for many organic producers, regardless of what they grow. For seed producers who took our survey, more than half (74 percent) identified weed control as a challenge. “When I [tracked production costs],” shared one seed producer, “weeding was one of the biggest costs.” Another seed producer said, “I think the biggest thing for us in organic is weed management. Just to be able to keep nice clean fields, you can keep that disease down.” Some seed producers pointed to the challenge of keeping weed seeds out of the seed they sell as well. One person commented, “It’s more difficult to control weed seeds and pests in the field, often resulting in longer cleaning time and more loss of good seed from a lot.”

Managing climate effects and adapting to climate change: Many seed producers commented on the difficulty of managing the effects of climate, with 77 percent reporting this as a challenge, and 71 percent specifically identifying this as a climate change adaptation challenge. Respondents pointed to fires and smoke affecting pollination and seed production, destructive winds and unpredictable freezes, and the lack of adequate rainfall. “It’s getting more difficult to control plant stresses [i.e., bolting],” shared one seed producer, while another pointed to there not being “enough people doing drought- and heat-tolerant work.” (See “Climate change threatens seed growers.”)

Sourcing appropriate seed cleaning and harvest equipment: Having appropriate equipment is a challenge for less than a third of all the seed producers, but the need is higher for those who work only on breeding and production activities, rather than processing and retailing. Of this subset of seed producers, 65 percent identify seed cleaning equipment as a challenge and 53 percent identify seed harvest equipment as a challenge. Comments from these respondents explain the challenge of “sourcing small- to medium-scale equipment in a region that doesn’t have a lot of vegetable seed production.” Producers suggest solutions, such as developing “appropriate small-farm technology,” identifying resources/programs for equipment cost sharing, and “sharing of techniques/tools.”

There’s also a scale issue. You really can’t find great equipment for a small-scale operation easily.”

Organic Seed Producer

Climate change threatens seed growers

Our seed-producer survey found that climate change is a major concern for seed producers, with 88 percent of respondents believing that climate change will significantly or somewhat harm agriculture during their lifetime. This sentiment was echoed in our researcher survey covered in Chapter 1, where 65 percent of respondents said they “often” consider climate change in their organic plant breeding and seed research, and 87 percent said that climate change will “somewhat” or “significantly” harm agriculture during their lifetime. “We are already seeing an increase in temperatures from climate change as well as more numerous wildfires, with their detrimental impact on air quality,” shared one researcher.

In September 2020, ten major wildfires emblazed western Oregon, consuming over one million acres in populous regions and nearly taking out irreplaceable seed supplies. As journalist Lynn Curry reported in The Counter, “For Northwest plant breeders and seed savers, warming temperatures due to climate change are a ‘selection opportunity.’ But it’s nearly impossible to select varieties with genetics adaptable to fire.”

The thick smoke from the wildfires diminished sunlight and cut temperatures 10–20 degrees. In turn, the temperature and conditions delayed the ripening of seed, affecting yields. Labor was also impacted, as the air was too unhealthy to breathe.

Oregon seed growers aren’t the only ones impacted by wildfires. Across the West, wildfires are becoming more frequent and intense. California seed growers know this all too well, along with other extreme climate-related challenges.

“While the fires are happening, they’re incredibly urgent and in your face,” said California-based seed grower Sorren of Open Circle Seeds. “For multiple years we had fires here, and dense smoke clouds—to the point where we didn’t see the sun once for a whole month—and we could see the impacts: some things didn’t ripen because of less sunlight, and we had fewer seeds.”

“But the fires are the least of it,” said Sorren. “They happen and then they’re gone. This year we didn’t have fires, but we had very extreme weather, and it’s all climate related.”

She added, “We didn’t have much rain. Usually we have rain in December through March and then it gets hot fast. This year we had a mild spring but no rain. Our last frost date is typically around May 15th, and this year we got a frost May 27th and then again the second week of June. A lot of crops were lost in that cold, and this meant we had a shorter growing season, too. After that frost in June, it went to triple digits for two months. Now, triple digits happen every year here, but this many days in a row is unusual. The ground was too hot for seeds to germinate. The sweet corn was beautiful and full size, but the plants had a lot of empty ears because pollen isn’t viable when temperatures are too high. Most of our tomato plants also didn’t survive.”

“Nothing is ever going to be the same again,” Sorren concluded. “Aside from growing seeds, I feel like my main job now is to watch for which varieties can survive the extreme climate chaos that we are facing. I also have to consider if I will still want to do seed contracts, or do I just want to grow for our own seed company so I’m not letting seed companies down? We couldn’t fulfill several contracts this year.”

Fortunately, Sorren said, they didn’t have problems accessing irrigation due to drought conditions, unlike a lot of farmers in California and their neighbors to the north in Oregon.

In April of 2020, as the growing season was getting started, Chickadee Farm owners Sebastian Aguilar and Kelly Gelino were told that instead of having access to their normal twenty-five weeks of irrigation water, only eight would be provided, due to the severe drought conditions in southern Oregon.

“This unprecedented reduction in available water took us, and everyone we knew, by surprise,” said Aguilar. “Despite 70 percent average snowpack, the parched mountains absorbed all the water and streamflow was minimal. Since we needed at least twenty weeks of water to grow the dozens of vegetable, flower, and herb seed crops in our farm plan, we were left with no choice but to call off the season.”